Dutch-Language Literature in Czech Language

Literary translations into Czech have a very long tradition. Among the oldest is the Bláznowstwije chwála, one of the first translations of Erasmus’s famous Moriae Encomium, made by the humanist Gregorius Gelenius (1460-1514) just a couple of years after the first 1511 edition. Due to Gelenius’s premature death the translation was published as late as in 1866. During the Thirty Years’ War, caused by the Czech anti-Habsburg uprising in 1618, the Bohemian Kingdom lost in fact its independence and thus Czech its position as a literary language. New chances came with the National Revival in the 1780s and the following decades.

Struggle for the own language

Report in Česká wčela of 7 February 1845 about Conscience's speech

The first translation of Dutch-written work into Czech was in fact the publication on 7 and 11 February 1845 in Česká wčela [The Czech Bee] of parts of a speech by Hendrik Conscience at the meeting of the Taelverbond [Language Alliance]. The first truly literary Dutch-written works published in Czech translation in 1846 and 1848, were three novels by Conscience, and translated into Czech from the popular German translation by Melchior of Diepenbrock in 1845. Till the end of the century many translations from Conscience’s works followed as Czech readers recognized their own problems with the German speaking elite in the Flemish struggle for equal rights for their language and culture in Belgium.

For a century, until the Second World War, the Czechs followed with great interest the struggle of the Flemish Movement for the emancipation of Dutch in Belgium. Until the First World War, there were regular reports on the fortunes of Hendrik Conscience, the most important literary leader of this movement in the second half of the 19th century. Edvard Beneš, later Minister of Foreign Affairs of Czechoslovakia and from 1935 to 1948 also the second president of the country, in a long article Národnostní boje v Belgii (The language struggle in Belgium; 1909) set the Belgian peaceful solution with the assimilation of Dutch in successive laws as an example for the Czech situation within the Habsburg realm.

Up until the First World War

From the late 1860s onwards, the need of Catholic publishers for relatively short novels with a good Catholic tenure, which they could use in their series for Catholic peasants and workers, resulted in a serious interest in the novels of Conscience and other similar Flemish and Dutch writers such as Renier Snieders and Johan Antonius Vesters.

The liberal translator and literary historian Václav Petrů also published several novels of non-Catholic writers (Nicolaas Beets, Jacob van Lennep) but his aim to start a whole series of such novels came to an end with his death in 1906. He and Alois Koudelka are the first Czech translators who translated directly from Dutch. Around the turn of the century, scholars gathered around the periodicals Lumír (Jaroslav Kamper) and Moderní revue (Arnošt Procházka) showed an interest in the Dutch naturalist novelist Louis Couperus and poets of the so-called Eighties Movement (Tachtigers). Responses to modern Dutch and Flemish authors were visible in the popular subscriber series 1000 nejkrásnějších novell 1000 světových spisovatelů [The 1000 most beautiful novellas by 1000 world writers] from the publisher Vilímek.

In the 1890s, an international interest in the work of Multatuli began, driven by the German translations of the anarchist Wilhelm Spohr. Czech Socialists were no exception. In the same period, several translations of anarchist and socialist political works were made, many of them presumably with the help of German translations. All these tendencies came to an end with the outbreak of the First World War.

Between both World Wars

Rudolf J. Vonka (1923)

The founding of the Czechoslovak Republic changed the situation for publishing houses as well. As the new state was predominantly a social democratic and liberal society, Catholic publishing houses lost ground and new houses such as the cooperative Družstevní práce [Cooperative Labour] and Sfinx were founded, both along with ELK [European Literary Club] of Bohumil Janda and Symposion of Rudolf Škeřík becoming the most influential publishers. Sfinx began as a house specialised in esoteric literature. This caused special interest in the writings of Frederik van Eeden on dreams. Frederik van Eeden was also interesting for the burgeoning Czech woodcraft movement, represented by Miloš Seifert who translated several of his works.

From the end of the 1920s onwards, two translators specialised in Dutch began their work. The first of them was the diplomat, left-wing protestant and Free Mason Rudolf J. Vonka (1877-1964), and the second, the more important Lída Faltová (1890-1944), the first professional translator of Dutch-written literature. She translated some 38 books from Dutch into Czech for important literary publishing houses such as ELK, Družstevní práce and Melantrich. In the 1930s, literary agencies began working – successively Centrum, Universum and Vincy Schwarz (1902-1942). The latter started as an employee of Centrum, went over to Universum after the bankruptcy of Centrum and finally founded his own agency. Thanks to his contacts with the Czech PEN-club, he had good contacts in the Low Countries and introduced several important writers in the Czech literary field. Czech news papers and literary periodicals regularly informed about Dutch and Flemish writers and reviews of Czech translations were written. The most frequently translated authors were the internationally acknowledged Flemish writer Felix Timmermans, and the popular Dutch writers Johan Fabricius and Antoon Coolen.

Lída Faltová (1938)

As of the middle of the 1930s, so-called Ruralism (rural wave) became an important literary movement in Czech literature. This strengthened the position of Coolen and Timmermans and made way as well for other Dutch and Flemish writers of rural novels such as Herman de Man, Jef Last and Stijn Streuvels, the latter being nominated in 1937 and 1938 for the Nobel Prize in literature. Growing political pressure from the Nazi regime on Czechoslovakia resulted in the translation of Hendrik Conscience’s main novel De Leeuw van Vlaenderen [The Lion of Flanders] in three different Czech translations and the warning essay of Johan Huizinga, In de schaduwen van morgen [In the Shadow of Tomorrow].

During the German occupation

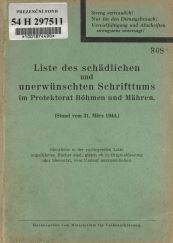

The secret index with forbidden books (version 1944)

The so-called Munich Treaty forced Czechoslovakia to cede the mainly German speaking border regions, the so-called Sudetenland, and Hungarian speaking regions in the Slovak Danube valley. Thus, Czechoslovakia lost its border fortifications, leaving a military indefensible state behind. President Beneš abdicated and the political system was in a chaos. This resulted in the liquidation of the last parliamentary democracy in Central Europe, the new ‘Second Republic’ was a kind of Austro-Fascist state that existed between October 1938 and March 1939. When a Slovak government was established, and a Slovak Assembly was opened in January 1939, Czecho-Slovakia became in fact a federal state. Hitler used growing tensions between the Slovak leader Msgr. Tiso and State President Hácha to force Tiso to proclaim an independent Slovak State guaranteed by the German Reich on 14 March 1939. One day later, Hitler forced Hácha to agree with the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. This was no puppet state like Slovakia but rather a semi-autonomous province of the Reich under control of German troops and the German Gestapo.

Censorship increased, more or less building on the foundations laid during the Second Republic. A list of forbidden works was published, containing also the works of Domela Nieuwenhuis and Jef Last. As the translation of ‘enemy’ literature – meaning English, French, Polish and Russian literature – was forbidden, publishing houses had to fill in gaps in their series. This meant a chance for Dutch-written literature, especially for Flemish rural novels. Publishing houses were careful and tried not to provoke the occupation authorities – thus, ready translations for which copyright was already paid such as Stiefmoeder Aarde [Stepmother Earth] by the Communist Dutch author Theun de Vries and Moeder, waarom leven wij [Mother, why do we live] by the Socialist Flemish author Lode Zielens were not published. It seems, however, that among the 2½ millions of books banned or destroyed by the Nazis from Czech public libraries, not all that many were translations of Dutch-language works. Due to the limitation of translated literature from other languages than German and growing paper shortages, the general numbers of translated works decreased in 1943 and 1944. Many works planned for the last two years of the occupation were published as late as 1946 after the liberation.

The Third Republic

The so-called Third Republic, covering the years 1945-1948 after the liberation of Czechoslovakia, was a special kind of ‘parliamentary people’s democracy’. In those years, nearly all German speaking inhabitants, over three million people, were forced to leave their traditional home country. They were transported to the American and Soviet zones of Germany or Austria. In Czechoslovakia, the pre-War parties were reconstructed with the exception of the Agrarian Party, this being the main political subject of the Second Republic. The Communists won the elections with an average result of 38% (40% in the Czech lands and 21% in Slovakia) and occupied the most important ministries in the coalition government, especially the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Information.

Using the post-war paper shortage (which was, however, artificially extended after 1946), the Ministry of Information forced the larger private publishing houses to hand over lucrative titles to other publishers. Nevertheless, during those years a significant number of translations from Dutch was published, as the deceased Lída Faltová was more or less successfully replaced by new translators: Ella Kazdová (1909-1982), Miroslav Drápal (1916-1991) and Milada Šimsová (1904-1992).

Towards a totalitarian regime

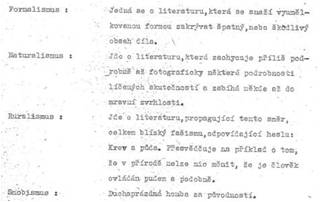

A sample of classification of unwanted literature (list 1953)

Using a government crisis in February 1948 caused by the Communist Minister of Interior when most of the democratic Ministers resigned, Communist Prime Minister Klement Gottwald decided to proceed as a minority government until the planned elections of May 1948. Under the pressure of Communist street riots, President Beneš accepted this, thus unwillingly enabling a complete Communist takeover. After the May elections, a genuine People’s Republic became a fact – censorship was renewed and between May 1949 and the end of the year the remaining private publishing houses were forced to merge into large state conglomerates – a process called ‘ressortisation’. Between May 1949 and April 1953, public libraries were cleaned from ‘hostile, defective, outdated and unwanted literature’ – more than 27½ million books (nine times the numbers the Nazis destroyed) were removed including works of the three most popular Dutch and Flemish authors Felix Timmermans, Johan Fabricius and Madelon Székely-Lulofs and all the prints of some 26 titles. Up until the end of the 1950s, nearly no new Czech translations of Dutch-language literature were published.

The new literary norms of ‘Sorela’, Socialist realist literature, were a culmination of efforts beginning at the end of the nineteenth century to restrict so-called brak [rubbish], meaning originally cheap editions of low brow literature, detective novels, pornographic novels and the like. In the 1920s, the idea of proletarian literature was born. This meant literature positively depicting the struggle of the working class towards an egalitarian, classless society. After the proclamation of Socialist Realism as the leading literary genre by the Union of Soviet Writers in August 1934, quarrels arose between the leftish avant-garde writers of, for example, Devětsil and the ideologically rigid hard core of the Communist Party. Zdeněk Nejedlý, a professor of art, was one of the main ideologists of Sorela – after the War he became Minister of Education and proclaimed Sorela the leading norm of literature in post-1948 Czech literature. As of 1948, translations from foreign literature, Dutch-language works included, were subject to this norm. Thus, a century of naturally free reception of Dutch and Flemish literary works, culminating in the last free years of the Third Republic, came to an end.

New beginnings: The era Olga Krijtová

Olga Krijtová (ca. 1960)

Nevertheless, the Czechs kept reading. Two years after Stalin’s and Gottwald’s decease in 1953, a young student finished her study of English and Dutch at Charles University. In 1956 she married the Dutch emigre Hans Krijt. In 1958, she published in Světová literature [World Literature] her first translation, of De onrustzaaier [The Troublemaker] by Willem van Maanen. In the same time, she got a job as lecturer of Dutch at the University. The lucky combination of a literary interested university teacher and a gifted literary translator in one person was a blessing for the propagation of Dutch-language literature. Krijtová translated during her long life more than 80 translations. Thanks to a certain ‘thaw’, Ella Kazdová, who had during the Stalinist 1950s serious problems due to her ‘bourgeois’ background, started to publish translations as well, mostly of rural novels for the Catholic Publisher Vyšehrad, then renamed in Lidová demokracie [People’s Democracy].

The 1950s and the early 1960s showed reprints of several successful novels of Johan Fabricius and Madelon Székely-Lulofs, translated by the late Faltová, ego-documents – especially the internationally popular Achterhuis diary by the murdered Jewish young woman Anne Frank. But as well new translations of Arthur van Schendel and, of course, the in all Socialist countries popular Dutch Communist writer Theun de Vries were published. After the Kafka-conference at Liblice in 1963, the progressive wave accelerated culminating in the 1968 Prague Spring. This gave a chance to writers of detective stories like Jan de Hartog and Remco Campert. The number of translations rose and the print runs as well. Thus, the 5th edition of the popular rural omnibus Vesnický lékař [The Countryside Physician] by Antoon Coolen had a print run of 160,000 copies. Historical and rural novels, but in Světová literatura a good choice of young writers like Jan Wolkers as well, were typical for this period. Many translations in the said periodical were made by students of Krijtová, several of them would later become translators themselves. A sign of the spring was as well that publishers could take back their old ‘bourgeois’ names, thus Svobodné slovo became anew Melantrich, Lidová demokracie was reborn as Vyšehrad. Even the big state houses that were founded in the 1950s out of confiscated private publishers received less formal names, like the State Publisher of Beautiful Books and Art that became now Odeon or the State Publisher of Childrens and Youth Literature that was renamed in Albatros.

The so-called Normalisation

In the night of 20/1 August 1968, the Prague Spring was crushed by Soviet troops occupying Czechoslovakia. Some 350,000 people returned their Party membership card in protest, Krijtová being among them. The regime answered with a publication ban that lasted till the end of the 1970s. In this period, a turn towards reprints and new translations of ‘good oldies’ like the The Hague novels by Louis Couperus or De oude klok [The Old Clock] by the Flemish writer Ernest Claes is visible. Furthermore romanced biographies like Felix Timmermans’ Adriaan Brouwer. A popular new group of translations concerned children’s books, mostly written by Krijtová’s friend Miep Diekmann. A new translation of Multatuli’s majestic novel Max Havelaar was published as well, and Světová literature published now regularly new translations of modern especially Flemish writers like Frans van Isacker, Hugo Raes, Julien van Remoortere and Ward Ruyslinck.

In the 1980s, the regime began to loosen its grip. The readers’ public asked rather easy reading novels like the historical novels of Theun de Vries and Johan Fabricius, or rural novels written by Antoon Coolen and Ton Kortooms. However, Odeon and the Party publisher Svoboda [Freedom] managed to publish books with a higher literary character as well, like Zelfportret of Het galgenmaal [Self-Portrait or The Gallows Meal] by Herman Teirlinck or De aanslag [The Attack] by Harry Mulisch. Finally, Olga Krijtová and her husband became the chance to present a short survey of Dutch literary history to the interested Czech reader in the publishing house Panorama that was published with some delay in 1990.

The Wild West years

The Velvet Revolution of 17 November 1989 that resulted in a collapse of the Communist regime unchained an enormous heap of energy as well in the publishers’ field In 1990, there were 550 publishing houses operating in the Czech Republic, publishing 4,136 works. Twenty years later, there were 5,474 houses publishing 17,054 titles. Especially in the first five years, when nearly no regulation whatsoever existed, many cheap reprints were published of good selling novels by long ago deceased authors.

In the same period, however, there were two attempts to found special Dutch series. The first was the Nizozemská knihovna [Dutch Library] of publisher Ivo Železný, who published i.a Harry Mulisch’s Twee Vrouwen [Two Women] and Bernlef’s Hersenschimmen [Out of Mind]. Due to economic circumstances the series was short living. It inspired, however, a couple of former students of Olga Krijtová to found a new series Nizozemská edice [Dutch Edition] in the publishing house for cinema Cinemax. In this series among others the faction books Het Belgisch Labyrinth [The Belgian Labyrinth] of Geert van Istendael and Een kleine geschiedenis van Amsterdam [A Little History of Amsterdam] by Geert Mak were published in Czech translation. This series was due to a lack of finances and the very specialized scope of the publisher short living as well but had a positive impact. The founders of the second series started in 1999 the still active society Ne-Be for the propagation of Dutch and Flemish culture in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and they caught the attention of the Dutch Foundation for Literature (then NPFLV).

Stabilisation of the book market

Veronika ter Harmsel Havlíková

The last year of the millennium, 1999, may be considered to be the turning point. On the one hand, new legal provisions clearly regulated the publishing market, bringing the Wild-West period to an end. On the other hand, the Dutch Literary Fund and, since 2004, the Flemish Literary Fund provided stable support for translations into Czech. Very important was as well that young translators, Veronika ter Harmsel Havlíková foremost, received Czech and Dutch awards for their translations. The number of translations consequently grew to at present around 15 translations per year, an amount that was reached in former times only in the last democratic years after the liberation.

In 1999, the Dutch writers Arnon Grunberg, Margriet de Moor and Cees Nooteboom came to the Prague festival Svět knihy [The World of the Book] to propagate the translations of their books, for Grunberg and De Moor this was a very successful action, as new translations of their work are regularly published by major Czech houses, often soon after the publication of the Dutch original. The translations are receiving often very good reviews – the fact that the translations are reviewed by literary periodicals and daily papers at all is in itself already a major step forward.

The range of Dutch-written literature translated into Czech since 1999 is relatively wide. It primarily includes quality fiction, which was mostly published with the help of one of the literary funds. Harry Mulisch, Arnon Grunberg and Cees Nooteboom established themselves in this area. This category also included authors of quality fiction, who, however, did not become permanently established in the Czech environment. These were thus more or less ‘random’ translation. In this context, one might mention, for example, Het Huis van de Moskee [The House of the Mosque] by Kader Abdolah (2011), Joe Speedboat by Tommy Wieringa (2008) or Donderdag namiddag, half vijf [Thursday afternoon. Half past four] by the Flemish writer Kristien Hemmerechts (2004).

Although Czech publishers tended to publish works by contemporary authors, there are exceptions. While books written by Margriet de Moor and Hafid Bouazza were published in Czech only a few years after the Dutch original, Willem F. Hermans’s novel De donkere kamer van Damokles [The Darkroom of Damocles], in contrast, only received a Czech translation more than fifty years after the original was published.

Trends in the last two decades

As a rule, without institutional support, commercially tuned titles have been published in the past two decades. In recent years, Czech readers have been particularly interested in the (autobiographical) novels by Raymond van de Klundert known as Kluun. We can also mention the humorous books of the author writing under the pseudonym Hendrik Groen.

Non-fiction has also gained more and more attention over the last twenty years. This category includes, among others, publications on prominent Dutch or Flemish personalities or local facts such as e.g. Kleine geschiedenis van Amsterdam (Amsterdam: A Brief Life of the City, 1999) as well as popular science books like Dierentalen (Animal Languages, 2019). In this area, there is also a clear interest in so-called ego-documents, which often focus on the topic of World War II. Eddy de Wind’s book Last Stop Auschwitz (2020) is an example. Dagboek van Anne Frank [Anne Frank’s Diary] also belongs to this category, which was repeatedly published in various translations and editions before and after the Revolution.

Books for children and young people got a stable place among Czech translations of Dutch and Flemish literature as well. Translations published between 1999 and 2021 include, among others, books written by Annie M.G. Schmidt Wiplala and Minoes (Minnie; both 1999), Francine Oomen’s novels for girls and reprints of older editions of the series about little Annejet by Miep Diekmann. Children's books on homosexuality have also recently attracted attention, such as Koning & Koning [King & King] by Stern Nijland and Linda de Haan (2013). In addition, Dutch and Flemish comics are published in Czech, both for children and adults. The book Sugar by Serge Baeken (2016) can be, for example, mentioned in this area.

Conclusion

Whenever translations of Dutch-language literature into Czech started relatively late, in 1846, there is a stable tradition of translations from then until present. Czech translations show a in the East Central European region remarkable high number of translations without break in the period from the 1880s till the 1940s, from the 1950s onwards tendencies are more or less comparable to those in the neighbouring countries, all making part of the so-called Socialist block.

The in this region normal connection between Chairs of Dutch Studies and literary translations was established in the Czech Republic in 1958 by Olga Krijtová with her first translation. Most present translators are her students or studied at one of the two other chairs in Brno and Olomouc. Thanks to the propagation policy of both literary funds and to the successes of several awarded translations, at present a relatively stable amount of around 15 titles a year is being produced for the Czech readers’ market.

References

Engelbrecht, Wilken (2015). “The formation of a literary canon of Dutch and Flemish literature in translation.” In: (ed.) Jana Engelbrechtová, Dutch – Flemish – Central European relations. Chapters from Cultural Relations between North-West and East-Central Europe. Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého, pp. 70-84.

Engelbrecht, Wilken, Zuzana Vaidová & Iva Jančíková (2015). Recepce nizozemské a vlámské literatury v českém překladu / Receptie van Nederlandstalige literatuur in Tsjechische vertaling. Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého. DOI: 10.5507//ff.15.24448350.

Engelbrecht Wilken (2018). “Die niederländischsprachige Literatur in tschechischer Übersetzung nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg.” In: (eds.) Lut Missinne & Jaap Grave, Tussen twee stoelen, tussen twee vuren. Nederlandse literatuur op weg naar de buitenlandse lezer. Gent: Academia Press, pp. 129-155 (Lage Landen Studies 10).

Engelbrecht, Wilken (2021). Van Siska van Rosemael tot Max Havelaar. Receptie van Nederlandstalige literatuur in Tsjechische vertaling tussen 1848 en 1948. Gent: Academia Press (Lage Landen Studies 14).

Harmsel Havlíková, Veronika ter (2015). “Institutionalisering van de productie van Tsjechische vertalingen van Vlaamse literatuur na 2000.” In: (ed.) Marketa Štefková & Benjamin Bossaert, Onbe/gekende verleiding. Vertaling en receptie van de Nederlandstalige en andere kleine Germaanse literaturen in Centraal-Europese context, Lublin: Wydawnicwto KUL, 153-163.

Havlíková, Veronika (2004). “Nederlandstalige literatuur in Tsjechië sinds 1990. Receptie van de Nederlandse en Vlaamse literatuur sinds de val van de muur.” Neerlandica extra muros 42 (3), 26-32.

Horáčková, Veronika & Marta Kostelecká (2021). “Literary Translations after the Velvet Revolution.” Czech and Slovak Journal of Humanities 2021/1, 54-62.

Krijtová, Olga, Ruben Pellar & Petra Schürová (1994). Bibliografie překladů z nizozemštiny do češtiny a slovenštiny od roku 1890 do roku 1993 / Bibliografie van vertalingen uit het Nederlands in het Tsjechisch en het Slowaaks vanaf 1890 tot 1993. Praha: Jednota tlumočníků a překladatelů.

Smolka Fruhwirtová, Lucie (2011). Recepce nizozemské literatury v českém literárním kontextu let 1945-2010. Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého.

Smolka Fruhwirtová, Lucie & Wilken Engelbrecht (2015). “Recepce nizozemské literatury v českém překladu”. In: (ed.) Wilken Engelbrecht et al., Dějiny nizozemské a vlámské literatury. Praha: Academia, 503-526.