Dutch and Flemish literature in Germany after 1945

Neither in Germany, in Austria, nor in Switzerland was there a literary 'zero hour'. The authors published in German translation after the war were primarily those who had been published before the Second World War: Timmermans, Claes, Streuvels and Coolen. In addition publishers banked on Emiel van Hemeldonck, André Demedts and Valère Depauw. Dutch representatives of literary movements like magical realism (Johan Daisne and Hubert Lampo) did not really pervade the German language area and their innovators remained virtually unknown. The latter is especially true for the so-called 'Vijftigers' who had dared to break with tradition via their physical, experimental poetry.

In the first decades after the Second World War, translations of the work of J. Presser and Marga Minco (and later Etty Hillesum) laid the foundation for the great interest in Dutch literature about the Second World War that would later follow. The translation of the The Diary of Anne Frank of course played a central role, which is just as controversial as successful in the German language area.

Georg Hermanowski

In the first years after the Second World War the literary developments in Flanders and the Netherlands were hardly observed in the German language area. There was little attention for "modern" Dutch literature, which Georg Hermanowski, a devout Catholic, tried to change in his own way.

Already during the war Hermanowski had made contacts in Flanders (a.o. André Demedts who recommended to translate Guido Gezelle). Hermanowski was convinced that "Flemish literature" had to be presented as an independent literature separate from Dutch literature (according to him the Dutch language community was not a cultural community). Essentially he had no interest in literature from the Netherlands.

According to Hermanowski the characteristics of Flemish literature were born from the synthesis between mystical piety and sensual joy of life; the fighting spirit, the strive for independence, the romanticism and the Catholic faith. He wanted to communicate this (presumed) archetypal Flemish disposition to the German language area. The choices he made for his conservative program were thus determined by the content not the form.

At the end of the 1960s Hermanowski held a quasi-monopoly of Flemish literature in German translation having realized more than 170 translations in 20 years. But with that he had also reached the peak of his success. At the end of the 1960s the influence of book clubs, which had played an important role in Hermanowski's program, was continuously diminishing and German readers were no longer primarily looking for recreational literature.

In the mid-1960s, Hermanowski, who was among other things met with increasingly strong opposition from the Dutch-speaking area, tried to save his business with translations of works by Paul de Wispelaere and the experimental Flemish author Ivo Michiels, but it to no avail. Frustrated Hermanowski had to end his career as a translator and retire as promoter of Flemish literature in the German language area.

Jürgen Hillner

Jürgen Hillner took over where Hermanovski had left off. In the second half of the 1960s, about fourteen translations by his hand appeared in the German language area. Hillner's program differed radically from Hermanowski's, not only because he also translated authors from the Netherlands (e.g. Jacques Hamelink (Horror Vacui, 1967), Willem Frederik Hermans (Die Schrecken des Nordens,1968 and Die Tränen der Akazien, 1968)), but also because he transcended all limits Hermanovski had established with the translation of works by Hugo Raes, Heere Heeresma, Jan Wolkers, Jef Geeraerts, Louis Paul Boon and Gerard Reve.

All of a sudden, Hillner's translations were identified with the erotic literature from the Netherlands and Flanders which turned them into a hoopla, but also no more than that. “Jaunty pornography” (Meier, 1970) turned out to be no guarantee for the future. With Reve the opinion prevailed that his work was "undoubtedly [...] poetry" (Meijer, 1970), this however did not lead to a breakthrough for the great Dutch author. Also Louis Paul Boon received good reviews, but in the end, as “unsparing portrayer of the self-destructive capitalist society” (G.J., 1976), only found his home base with a publisher in the GD.

The Sorrow of Belgium

A next important step in the history of Dutch literature in the German-speaking world is the publication of the translation of Hugo Claus’ De verwondering (Die Verwunderung, 1979). The translation did not immediately lead to a breakthrough in the German language area for this great Flemish author but was important in that it was relatively 'well' received despite being very “literary” (see Hugo Claus, 1979). The publication of Die Verwunderung by Suhrkamp was also of importance because it was not a translation by Jürgen Hillner.

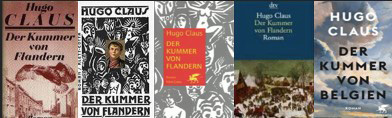

Slowly it wasn’t mediators and translators anymore who set the course but publishers. At first, with all the consequences this entailed. It was thought that one had to reconnect with the past and the success of Timmermans and the like. It is no coincidence that Claus' masterpiece Het verdriet van Belgie [The Sorrow of Belgium] was translated in 1986 under the title Der Kummer von Flandern. With this title the book even saw a second edition and was also published as a paperback. In 2008, in the context of a new translation, the book appeared again with the same publisher but now under the title Der Kummer von Belgien. In the following years more titles by Hugo Claus appeared in the German language area. However, the all-rounder and language virtuoso Hugo Claus never enjoyed the same success in the German language area as in the Dutch language area.

The Assault

When Das Attentat [The Assault] appeared in Germany in 1986, the Harry Mulisch was not yet a household name there. In the mid-1980s the author already had a few translations to his name (Das steinerne Brautbett [The Stone Bridal Bed], 1960; Der Diamant [The Diamond], 1961, Schwarzes Licht [The Black Light], 1962; Zwei Frauen [Two Women], 1982) but these translations did not reach a wide audience.

This definitely changed with the publication of Das Attentat and Höchste Zeit [Last Call] (1987) by Hanser. When Flanders and the Netherlands were guests of honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1993, Harry Mulisch was already a star and remained one from then on.

Mulisch's Entdeckung des Himmels [The Discovery of Heaven] (1993) is a real bestseller. In 2021 at Rowohlt the thirtythird edition is on sale!

Cees Nooteboom

Although Cees Nooteboom’s carrier developed equally difficult at first as that of Claus and Mulisch, more than 260 publications of Cees Nooteboom appeared in the German language area by now.

The first translation of Nooteboom's work in Germany, Das Paradis ist nebenan [Philip and the Others] (1958), went unnoticed. Things went hardly different with Rituale [Rituals] which appeared almost 30 years later (1984) with Volk und Welt.

It was only after the publication of Berliner Notizen [Berlin Notes] (1991) that Nooteboom became a household name. At the time the author was staying in Berlin on a grant from the DAAD [German Academic Exchange Service] and closely followed the 'fall of the wall'. Excerpts from his book, that was going to be published with Suhrkamp, were regularly published in the Berlin newspaper Die Tageszeitung. Nooteboom was the talk of the town.

Nootboom's absolute breakthrough was sealed not by the award of the Literaturpreis zum 3. Oktober but by a comment of Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the television program Das literarische Quartett. In connection with the translation of Het volgende verhaal [The following story], the boekenweek gift of 1991, Marcel Reich-Ranicki said:

“It made a deep impression on me, and I deeply regret that I overlooked all and not read Nooteboom's previous books. This is a very important European writer, and one of the most important books, perhaps the most important that I have read this year. [...] The story is brilliantly written. [...] I was deeply touched by the book, and when I can recommend a book—because now Christmas time is coming along, and people will buy books, and they will buy the wrong ones—then I say: it's not a bestseller, but it should become a bestseller. [...] I recommend it because it is real literature. [...] I like to talk about the ambiguity, that is the mark of literature, here it is featured, the ambiguity, here exists literature and poetry. And I am deeply impressed by this Nooteboom; looky here, the Dutch have such an author!” (Eickmans, 1991) (Das literarische Quartett 16 - www.youtube.com/watch)

Within a few weeks, more than 80,000 copies of Die folgende Geschichte had been sold! Since then, Suhrkamp has published the complete works of Nooteboom in 10 volumes.

Frankfurter Book Fair

The 1993 Frankfurt Book Fair at which Flanders and the Netherlands were guest of honor for the first time meant an "unprecedented boost" (Missine, 2018, p. 11) for Dutch-language literature in German translation. The same goes for the 2016 fair, where even more translations were presented (according to Missine 180 books for adults and 129 books for children and young adults).

Yet there is a difference between the fairs of 1993 and 2016. While the first fair was well 'prepared' (interest in Dutch-language literature had been growing in the years before) in 2010 the success of Dutch-language literature in the German language area was on a downward trend. With the fair in 2016, the number of translations did double, but this effect was not long-lasting.

Apparently, people in the German language area are still not convinced that "our literature is one of the richest and most beautiful in the world" (Hugo Brand Corstius in Missine, 2018, p. 15). Seemingly something still remains to be done in the German language area.

(Herbert Van Uffelen)

References

Eickmans, Heinz: Bestseller Nooteboom - ‘Sieh da, die Holländer haben einen solchen Autor!’ In: Nachbarsprache Niederländisch, Nr. 2, 1991, S. 132.

G.J.: Wo menschliche Gefühle verkümmern. In: Eichsfelder Bekleidungswerke, Nr. 6. 30. März 1976.

Hugo Claus. In: Fränkisches Volksblatt, 30. Nov. 1979.

Meier, P.: Ein ‘poète maudit’ als Staatspreisträger. In: Tagesanzeiger, 8. März 1970.

Missinne, L.: Van 1993 tot 2016. Nederlandstalige literatuur in Duitse vertaling tussen de twee Buchmessen. L. Missinne & J. Grave (Ed.). Tussen twee stoelen, tussen twee vuren. Nederlandse literatuur op weg naar de buitenlandse lezer. Gent: Academia Press 2018, pp. 11-30.