Dutch Literature in Poland

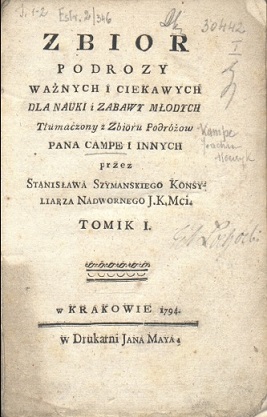

Title page of the oldest known translation form Dutch into Polish: "Zbior podrozy ważnych i ciekawych dla nauki i zabawy młodych. Tłumaczony z Zbioru podróżow pana Campe i innych przez Stanisława Szymanskiego", Kraków 1794.

For many years the translation of Journael van Bontekoe (an account of a trip to the East Indies) printed in Wrocław in 1805 has been regarded as the oldest translation from Dutch into Polish but recent research has moved that date to 1794 when the diary of Gerrit de Veer form his voyages with Willem Barentsz in search of the Northeast passage has been published in Polish. In both cases the text is an example of travel literature and was included in a collection of different stories with similar content. Both books have been translated from German “for the education and enjoyment of young people” as the subtitle of both collections states. It is significant that it is these two books that mark the beginning of the Polish reception of Dutch literature, as they also largely characterise the subsequent interest of Polish readers in the literature of the Low Countries. On the one hand, it is literature for young readers that makes up the majority of books translated into Polish. On the other hand, it is clear that many particularly classic works appear in collections of fragments or anthologies.

Despite long-standing historical connections, interest in Dutch literature in Poland was negligible in the first half of the 19th century. This may be due to the absence of Poland as a country on the map of Europe. The Partitions of Poland, conducted by the Habsburg monarchy, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Russian Empire between 1772–1795 ended the existence of the state. The Germanization and Russification of Polish school system resulted in illiteracy amongst the younger generations. It has also led to a focus on national themes in own literature and, consequently, to a significant reduction in translations of particularly culturally distant literatures.

The first upsurge of interest can be seen in the second half of the 19th century (translations of Conscience) and especially at the turn of the century. During this period, translators increasingly turned to foreign literature, especially literature whose themes were related to the far-reaching social changes of that period. During this time, Polish editions of books by authors such as Multatuli, Coupersu and Heijermans were published. The inter-war period is mainly characterised by translations of women's literature (and the great success of Jo van Ammers-Küller, sometimes called by Polish critics the greatest novelist of the time).

Direct translations

It was only after the Second World War that translations of Dutch literature ceased to be based on German versions. Literally few previous direct translations only confirm that for translators of literature, German was usually the language of the source text. In the 1960s and 1970s, Dutch studies began to develop in Wrocław and Warsaw. This allowed the books to be translated from the original. Although most translations focus on the literature of the so-called canon, it also happens that lesser-known texts find their way to Polish readers. In the second half of the 20th century, Polish bookshops offered works by Harry Mulisch, Jan Wolkers, Hella S. Haasse or Hugo Claus. In addition to these great classics, there were also works by lesser-known writers, such as Eddy C. Bertin, Robert Hans van Gulik, Janwillem van de Wetering. It is not only prose that is well represented, also many poets have lived to see Polish translations, such as J. Bernlef, Paul van Ostaijen and Willem Roggeman.

Popular genres

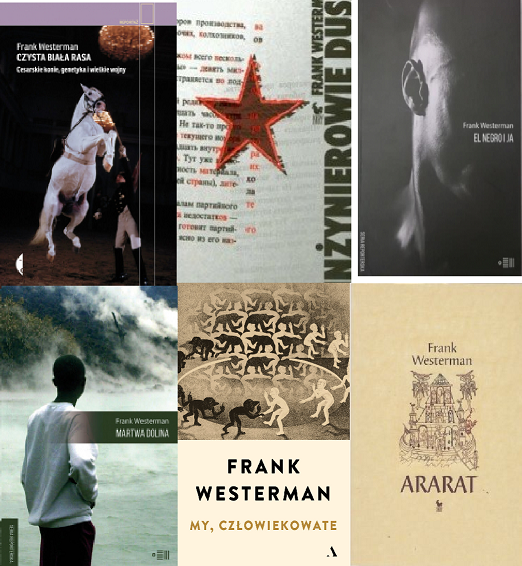

The first decades of the 21st century have been marked above all by a growing interest in new types of literature, especially non-fiction and literature for children and youth. The first type is represented by translations of reportages by Geert Mak, Lieve Joris or Cees Nooteboom, among others. However, it seems that in this group, the most popular in Poland is Frank Westerman, whose as many as 6 books have been translated by 2022. Children's books are mainly represented by such big names as Annie M.G. Schmidt, Dick Bruna, or Guido Van Genechten, while among the authors of youth literature we find Anna Provoost, Anna Woltz and Simon van der Geest.

A popular genre is also the short story. Perhaps this is the reason why many anthologies with short stories from the Netherlands and Flanders have already appeared in Poland. The first collections appeared in the 1970s and the most recent was published in 2019 (Napitki & Literatura). Initially, authors from the Northern and Southern Low Countries were presented in separate collections, but several anthologies present a cross-section of literature from the Dutch language area.

Poetry published both in anthologies and translations of individual volumes is also very well represented. Works of the classics (Lucebert, Hugo Claus) as well as recent poetry (Maud Vanhauwaert, Miriam Van hee, Menno Wigman) are translated.

Covers of Polish translation of Westerman's books

About Dutch literature in Polish

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mentions of Dutch writing were common in studies of global literatures, lexicons and encyclopaedias. The first significant study was Wladyslaw Markowski's 1932 sketch of a translation of Jacob Prinsen's Geillustreerde Nederlandsche Letterkunde (1924). In the 1980s, when Dutch studies began to develop in earnest, Marian Szyrocki published a textbook for students entitled Szkice z literatury niderlandzkiej (Sketches from Dutch Literature, 1983). Two years later, another history of Dutch literature by Dorota and Norbert Morciniec appeared in the form of a textbook (a modernized but shortened new version was published in 2019).

The most important contemporary studies are by far Andrzej Dąbrówka's Słownik pisarzy niderlandzkiego obszaru kulturowego (Dictionary of writers of the Dutch cultural area, 1999) and the two-volume comprehensive Widzę rzeki szerokie. Z dziejów literatury niderlandzkiej (I see rivers wide. From the history of Dutch literature, 2018) edited by Jerzy Koch and Piotr Oczko. This latest publication is a collection of texts by 10 authors on selected themes of old and modern literature, arranged chronologically. One of the last chapters presents a bibliography of translations of Dutch literature, but is limited to book publications only.

An important role in promoting Dutch literature to Polish readers is played by the Literatura Foundation, which presents the latest publications, excerpts from translations, reviews, and interviews with authors on its website 'pisarze mówią'. In addition, the Foundation also operates offline by engaging in meetings with writers from the Netherlands and Belgium in Poland. The Foundation also works in the opposite direction by promoting Polish literature in Dutch-speaking countries.

(Małgorzata Dowlaszewicz)