Dutch non-fiction in Romania

Perhaps Dutch non-fiction was, and still is, at least as popular as the best-selling novels and poetry volumes coming from the Netherlands. In fact, when given time to reflect on such a matter, names like Erasmus of Rotterdam or Spinoza would invariably pop in one’s head. It is not therefore much to our surprise that in 2005 a study[1] based on data from around 70.000 libraries revealed that the four most present books in world’s libraries, coming from the Netherlands, were Anne Frank’s diary, Het Achterhuis, Thomas a Kempis’ Imitatio Christi, Erasmus’ Laus Stultitiae and Corrie ten Boom’s life story. They might not all be written in Dutch, but they certainly are representative for the Dutch non-fiction tradition.

To begin with, the first Romanian translations of Dutch non-fiction were strongly linked to the sincere interest a few teachers or professors showed for Dutch pedagogy or popular science handbooks, as early as the 1930s and 40s[a1] . One of the most interesting stories from that period follows engineer Ștefan Georgescu-Gorjan’s eventful life and achievements. Born in Craiova, Romania, in 1905, he was raised by his parents, Stanca and Ion Georgescu-Gorjan, who both of them were acquaintances of Romanian modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. Although he graduated from the Polytechnical University of Bucharest, Gorjan had always been a fervent visitor of art galleries. After a 6-month training in Vienna, he then came back to Romania, where he became chief engineer and assistant director in the mining district of Jiu Valley. Travelling on business, he met Brâncuși in Paris in 1934 and little by little became close to the artist. In those days, Brâncuși was planning his sculptural ensemble at Târgu Jiu. After coming up with several technical solutions for the construction of The Endless Column, it was in 1937 that the two started working together on the artist’s most magnificent project.

But apart from his career as an engineer and professor of engineering, Ștefan Gorjan was also a polyglot and a prolific author, translator and editor of tens of technical handbooks. While he mainly translated from German, he even adapted two titles from Dutch: Physics for young people - 200 simple experiments (1947) and Chemistry for young people (1949), originally by Jan C. Alders, a renowned author of popular science and do-it-yourself books himself. After he had moved to Bucharest and established his own publishing house, „Gorjan”, the new communist regime closed down all privately owned publishing houses in 1948. Following a mock-trial, Gorjan went to jail for four years. When he got out, he committed himself to setting up a personal Brâncuși archive and participated in several preservation projects focused on the ensemble in Târgu Jiu.

During the first decades under communism, there was a clear turn in terms of interest for literary translations from Dutch. As expected, literature regarded as valuable was selected on political, Marxist criteria and very often accompanied by prefaces as such. It is probably because of that and the isolation from the „decadent western thought” in these times also that many intellectuals focused on Renaissance and Humanist philosophy. It was then that Dutch works of philosophy such as Ethics by Spinoza (1957), In praise of folly and On war and peace by Erasmus (1959, resp. 1960) and On the Law of War and Peace (1968) by Hugo Grotius found their way to the public via professional literary translations from Latin.

Under communism

But things were soon about to change, once the first professional translator from Dutch into Romanian set about working in the late 50’s. H.R. Radian translated many classics of Dutch fiction by Multatuli, Vondel, Louis Couperus, Hugo Claus or Hella Haasse, but he nevertheless found non-fiction, especially biographies of painters and specialty literature interesting. Jan Steen, Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt are the leading figures of Dutch 17th century art and also the painters whose biographies became accessible to the Romanian public, with the help of Radian’s tireless efforts. Perhaps the most striking endeavor of the kind was his 1977 translation of Carel van Mander’s Schilder-boeck from the original early-modern Dutch. All of his translations of books on Dutch art were published by the Meridiane Publishing House, which was then establishing its famous series Biblioteca de Artă (The Art Library), a collection of fundamental monographies, biographies and studies focused on Wolrd’s Art. So magnificent was it that no other Romanian publishing house has yet managed to achieve such a rich portfolio of art history and theory books. But information as such may not surprise us when we learn that H.R. Radian’s first love was architecture, a profession that deeply influenced his vision and choices as a translator and promotor of Dutch literature in Romania.

Today he is very often remembered as the translator of Johan Huizinga into Romanian. His versions of Autumntide of the Middle Ages (1970, 1993, 2002, 2021), Erasmus (1974), Homo Ludens (1977, 1998, 2003, 2012) and The Dutch Civilization in the Seventeenth Century (1991) have already seen several editions by different publishers and have now been quoted hundreds of times by various Romanian leading intellectuals. Johan Huizinga has probably been, alongside Anne Frank, the most famous Dutch author translated into Romanian so far. A fragment of his Homo ludens has even been included in one of the 9th grade textbooks („Corint” Publishing House, 2004) that is still used by high-school teachers of Romanian language and literature and read and studied by hundreds of students from all around the country.

H.R. Radian may have been the first Dutch translator from our country to pay that much attention to the non-fiction coming from the Low Countries, but certainly not the only one. It was also in those times that a translation of Van Gogh’s letters was published by the same publishing house Meridiane (1981). Although Constanța Tănăsescu, the translator, states in her foreword to the translation that she only made use of English, French and German sources and the book consists only of a selection of the letters, her work became quite popular and the The Letters have therefore seen another two later editions (Dear Theo, 2008, 2016, Editura ART) until now.

New beginnings

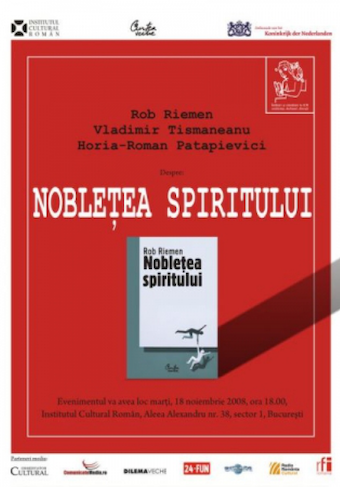

More recently, Gheorghe Nicolaescu, a leading translator of fiction, has also had his share of non-fiction by translating Rob Riemen’s philosophical essay Nobility of Spirit. The book was launched in the presence of Rob Riemen himself, accompanied by Vladimir Timsăneanu and Horia-Roman Patapievici, two prominent Romanian intellectuals.

But Dutch non-fiction is not represented in our country by art and philosophy books only. Books such as Anne Frank’s diary (Het Achterhuis/Jurnalul Annei Frank, Humanitas, 2011, 2016, 2018, translated by Gheorghe Nicolaescu), Etty Hillesum’s diary and letters (Jurnal (1941–1942). Scrisori din lagărul de la Westerbork (1943), Humanitas, 2021, translated by Gheorghe Nicolaescu) or Eddy de Wind’s story of survival (Eindstation Auschwitz: Mijn verhaal vanuit het kamp/ Auschwitz, ultima stație: Povestea mea din lagăr, 1943–1945, Humanitas, 2021, translated by Alexa Stoicescu) have also found their way to the public in the last decade. It is probably the ever-lasting memory of war or the stories we have been told by our grandparents about those days that arouses the interest of the Romanian public for diaries and memoirs of such kind.

On a different note, more recently, „Editura Litera”, a publishing house originary from The Republic of Moldova, has translated various self-help books and albums by authors such as Elise De Rijck (10 titles), Leo Bormans, Ivan Moscovich or Geert Verbanck. Some of this books benefited from a translation from the original Dutch text, by Ovidiu Achim, while the others were translated via the English version. Maybe, the most important titles to have appeared at Editura Litera until now are Rutger Bregman’s bestsellers Utopia for Realists (Gratis geld voor iedereen: en nog vijf grote ideeën die de wereld kunnen veranderen/Utopie pentru realiști, 2020, translated from English) and Humankind (De meeste mensen deugen/Homo Sapiens: O istorie plină de speranță, 2021, translated from Dutch by Elena Iurea and Ovidiu Achim).

Varying from classics of philosophy to art, anthropology and (cultural) history books (and with an added twist of self-help, popular science and contemporary thinkers), the wide spectrum of Dutch non-fiction has yet managed to appeal to both the Romanian intellectuals and to the broader public.

(Ovidiu Achim)