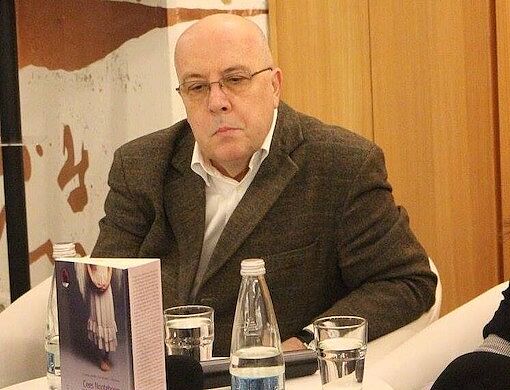

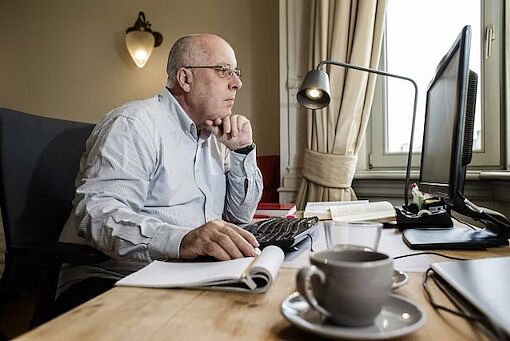

Gheorghe Nicolaescu

Arguably the most renowned literary translator from Dutch (and German) into Romanian, Gheorghe Nicolaescu has been the leading promoter of Dutch culture in Romania for the past 30 years. His list of translated titles is quite impressive, ranging from symbolist poetry to all-time classics such as Anne Frank’s diary or Cees Nooteboom’s The Following Story and, last but not least, to contemporary bestsellers such as The Dinner by Herman Koch and even non-fiction such as Rob Riemen’s Nobility of Spirit. In fact, his portfolio is wider than that, also including works by Louis Paul Boon, Connie Palmen, Bernlef, Arnon Grunberg, Harry Mulisch, Etty Hillesum and others.

Apart from that, he has also had a significant career as teacher of German at one of the best high schools in Bucharest, and then as a professor of Dutch and German languages at the University of Bucharest. He retired in 2018 as associate professor, leaving behind a legacy of many generations of students that have studied Dutch thanks to his efforts.

But his first encounter with the Dutch language was a sheer coincidence. He went to Leipzig at the beginning of the seventies to study German language and literature, where he also needed to choose a minor. At that time, Swedish seemed to him the most interesting, although things were soon about to change. (Un)fortunately, the only professor of Swedish at the university had taken a year off, which led the young Nicolaescu to follow a different route of the Germanic languages. He opted for Dutch instead, a decision that would prove to be the right call and that has essentially changed his life.

After completing the compulsory military service, Gheorghe Nicolaescu was given the opportunity to translate the Dutch poems from an anthology dedicated to European Symbolism. Many Western novels might have passed as ill-famed for the communists, but as he puts it, poems were maybe „less offensive” and, most probably, more difficult to understand for the authorities in charge of literary censorship. The rhymes of Leopold and Van Langendonck were, needless to say, a breath of fresh air, but also a very good practice for his later career. For prose it was quite the same, as the first novels he translated, De bende van Jan de Lichte by Louis-Paul Boon and De trap van steen en wolken by Johan Daisne, needed to be considered “not dangerous” in order come out.

Before and after 1989

A keen observer and bitter critic of the Romanian society and its evolution throughout the last four decades, Nicolaescu would often point out the major changes of the book market in our country. As he remembers, during the communist regime, the publishing houses would issue some 30 000 copies of a translation from an „exotic” language. Sometimes even 40 000 or 50 000. This might sound exaggerated from today’s perspective, but (foreign) literature was then one of the very few means of entertainment. Moreover, translations were regarded as one of the very few ways of keeping in touch with the Western world. But the revolution has changed everything, as he puts it.

The first decade after the fall of the Iron Curtain brought about an afflux of newly established publishing houses, which would most often focus on literature written in English. The quality of both the published works and the translations was questionable, but meant to give the public the once forbidden fruit. However, it was as early as 1993 that Gheorghe Nicolaescu managed to translate into Romanian Cees Noteboom’s The Following Story, an international bestseller and, at the same time, on the initiative of Coen Stork, the beloved ambassador, he worked on a literary magazine dedicated to The Netherlands and its culture.

"We only publish novels – not too thin, not too thick – so that the readers could afford them. And unless they are American, it would be of a great advantage to have been translated in more than twenty languages or at least to have won some international prizes… and… we almost forgot … It would be really nice if we could get financial aid for the publishing costs."

The turn of the millenium brought about better times for the literary translations of Dutch literature into Romanian. Connie Palmen (The Laws), Arnon Grunberg (The Story of my Baldness), Harry Mulisch (Siegfried), Bernlef (Out of Mind) are just a few names Gheorghe Nicolaescu made available for the Romanian public in the first decade of the 21st century. For his extraordinary merits as translator and promoter of the Dutch culture in Romania, Nicolaescu received the Translation Prize of the Dutch Foundation for Literature (Nederlands Letterenfonds) in December 2008. Perhaps his most successful translation yet is his 2011 version of the complete edition of Anne Frank’s diary, a best seller for every generation that has now seen five editions (including an anniversary one), an audio book and a visual adaptation for children.

“Mulisch is a wizard. He knows that art should be artificial in order to achieve something. He creates his own universe, his own reality, which I highly admire in him.”

Nooteboom remains to this day one of the authors that he translates with great pleasure, due to his poetic use of the language. However, as Nicolaescu stresses out, it is with the greatest precision that Nooteboom writes in Dutch. Delightful as it is, his prose is challenging to translate, because of its wide use of quotations in different languages. More recently, Etty Hillesum’s diary has also proved to be demanding, as Nicolaescu still recalls the days of struggle when he was trying to find the best solutions to match her uniquely flowing style. The result is a translation very close to the original text, which manages to render the stream of her thoughts, without being difficult to follow.

In the last years, Nicolaescu seems to have mainly focused his efforts on contemporary best sellers. Herman Koch (The Dinner), Hendrik Groen (The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen), Marente de Moor (The Dutch Maiden), as well as a few poems by Tom Van de Voorde are just a few of his more recent literary projects.

(Ovidiu Achim)