Dutch literature in Slovakia

The aim of this entry is to give a concise history overview of the reception of Dutch literature in Slovakia.

Since this is a historical overview, we should first take into account that the demarcation of the historical periods will also have some implications:

Firstly, a demarcation always implies a certain simplification: we assume that demarcating a certain period implies a certain turnaround in translation policy and/or the political situation of our country, but of course we must realise that such boundaries are always drawn arbitrarily to some extent.

Secondly, we bring the story of Dutch literature abroad, in this case to Slovakia. This makes it logical that historical boundaries are drawn on the background of historical developments in Slovak history. Slovak history is closely intertwined with the Habsburg Empire in the early modern and modern era and as such has cross-references with the reception history of the countries and ethnic minorities that were part of this empire, primarily the German speakers, but also the Czechs, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Romanians, Rusyns, Croats, Serbian and Italian minorities. In the modern period, after 1918, an independent First Czechoslovak republic arose under the triumvirate of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, the first Czechoslovak president, Edvard Beneš and the Slovak Rastislav Štefánik. Soon after Štefánik's death arise movements for more autonomy for the Slovak part of the republic, which results in a collaboration with the Nazi regime and the foundation of the clerofascist Slovak state (1939-1944) under the leadership of the priest Jozef Tiso. The history continues in the Second Czechoslovak Republic, until the socialist government seized power in 1948 and Czechoslovakia belongs to the Eastern Bloc until 1989. Apart from the short interlude during the Second World War, it is only from 1993 onwards that we can speak of an independent Slovak republic and thus of a truly separate accompanying reception.

Thirdly, there are trends that are taking hold across Europe after the 1990s. Various literary sociologists (e.g. Heilbron and Sapiro, 2007) have developed a sociology of literary translation against the backdrop of language policy. In the field of literary translation and promotion by the literary funds, tendencies of convergence can be observed (the same books are promoted, for instance through international book fairs) and divergence takes place through certain individual translators, intermediaries, university courses, policy of publishers in the countries themselves.

As far as history is concerned, it is customary to refer to the joint republic of Czechs and Slovaks in one word as Czechoslovakia before 1989, but after the fall of the Wall a dispute arose, the so-called hyphen war, because of which the republic was presented as Czecho-Slovakia for three more years. During the Habsburg Empire the territory of present-day Slovakia did not exist as an independent area but was part of the Kingdom of Hungary and the areas inhabited by ethnic Slovaks were referred to as Upper Hungary. Czechs lived in the so-called Kingdom of Bohemia (coronation city of Prague) and other Czech speakers still lived in the Margravate of Moravia (capital Brno and Olomouc bishopric) and the Duchy of Silesia.

As far as the concept of reception of Dutch literature in Slovakia is concerned, we can problematise the term Dutch. Adam Bžoch, in his small history of Dutch literature (2010: 9-10), firstly defines Dutch as a concept that encompasses the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but secondly it can also encompass the historical part of the Benelux where Dutch was spoken, roughly covering the present-day Netherlands with the northern part of Belgium. As far as the area of Dutch literature is concerned, we should always keep in mind a certain ambiguity in the definition of Dutch literature. On the one hand, the adjective means that geographically it concerns the Dutch kingdom (and therefore, by definition, excludes everything from Flanders), on the other hand, the adjective can refer to the language and thus include literature from the Netherlands and Flanders (and thus the Belgian-Dutch language variety). This ambiguity continues to exist beyond national borders. Not infrequently we find translators from "Flemish", "Belgian authors", Dutch authors, sometimes the concept pairs of Dutch literature, literature from Netherlands or Flemish and Dutch literature.

Since it is impossible to take a unified position in this conceptual discussion, we take as a starting point in studying the reception just as in Homola's article (2018: 87) that the reviewed reception, the source texts of the novels, poetry, plays, literary non-fiction, etc. were originally written in a variant of Dutch. They were then translated into Slovak as the target language, whether or not through a third language, which in the past was usually German or French, but even today translations still take place through an authorised, usually English translation.

In the beginning there was ... Conscience

Engelbrecht (2016: 239), who explains the case of Conscience in Czech translations, notes that he is the first Dutch-language author to be translated into Scandinavian languages and Czech, Hungarian and Slovak in Central Europe. He points out the great influence of Melchior van Diepenbrock's German translations from 1845 onwards (Engelbrecht 2016: 244), which probably also led to two Slovak translations in 1862. The first is a translation of De geschiedenis van graef Hugo van Craenhove en van zijnen vriend Abulfaragus into Deje hrabäťa Hugo van Kraenhove a jeho priateľa Abulfaraga and the second is In´t Wonderjaer 1566 as Zázračný rok 1566. Dejepisný nastín z XV. stoletia. They were published by a private printing house in Budín (today Buda/pest) in Hungary, namely that of Martin Bagó, who also printed calendars within Slovak Catholic circles (see: Kačírek 2016: 52). In this period, the Slovak free printing press was curtailed in the Slovak territory itself because in the Hungarian part of the dual monarchy, the Hungarians pursued a strict language policy of magyarisation. Buda, as part of Budapest, was certainly a power factor in the Slovakian literary field. In this city there were several reading circles, literary societies and among others the reverend Ján Kollár was leading a group of Protestant intellectuals.

At any rate, in the case of Slovakia too, Engelbrecht's conclusions about his investigation of Conscience's reception in the Czech Republic are partly confirmed: at least one collection from 1864 was translated from German into Slovak (i.e., Diepenbrock's influence is present here), there was also the influence of the Catholic publishing houses (see Engelbrecht 2021: 70-75), which in the case of Slovakia were located in Budapest, and at first these translations were not published in book form but as collections from calendars and almanacs or cheap editions, which does indicate that Conscience was not necessarily considered a literary writer.

Except for the five translations by Conscience (see DLBT and www.kgns.info/recepciask), no further translations were recorded in the nineteenth century. However, Engelbrecht (2021: 53-54) points out a poorer and incomplete accessibility of archives and bibliographical material in the case of Slovakia in contrast to the Czech situation, so more research is certainly needed, it is not excluded that more translations will be found. At the beginning of the twentieth century, some translations were found in Slovak newspapers and periodicals, such as short texts from J.J. Cremer, Herman Teirlinck, Multatuli and Herman Heijermans.

The period of Májeková

Ernest Claes´Herman Coene was the first novel translated straight from Dutch into Slovak.

Júlia Májeková studied Slovak and German at Comenius University during the Second World War, when several Flemish authors of the so-called regional literature or heimatliterature were translated into German and distributed within the German literary field. She translated Herman Coene by Ernest Claes in 1944 on the advice of her teacher Jozef Felix, a novelist at the Faculty of Arts. We can consider Májeková as the first translator who translated Dutch literature originally from Dutch into Slovak. Nevertheless, some other translators were also known, who may have worked through French, German or later authorised translations from English. (Bossaert 2018: 84)

Characterising the translation oeuvre of Májeková (who also translated from German) is closely related to what was allowed before the stricter communist censorship. Nevertheless, she succeeded in making a good cross-section of literature from Flanders and the Netherlands accessible to Slovak readers, including both canonical authors (Couperus, Mulisch, Claus), but also innocent children's authors (Terlouw, Diekmann), and writers who were known as friends of the regime such as Theun de Vries and A. den Doolaard. As editor of the publishing house Tatran, she could also recommend book titles relatively easily. Many translations of poetry, short stories and fragments of novels were also published in the translation-oriented journal Revue svetovej literatúry (The Review of World Literature). (Engelbrecht and Maňáková 2006: 25-26) It is worth mentioning that Májeková received the prestigious Martinus Nijhoff Award at the Dutch Embassy in Prague in 1978 and that she received the prestigious Ján Hollý Translation Award in 1974 for her translation of De Goden gaan naar Huis by A. den Doolaard.

Literary translations after 1993

Adam Bžoch - one of the most active literary translators from Dutch

After 1993 the reception of translated literature into Slovak coincides for the most part with the translation career of Prof. Adam Bžoch. Bžoch studied German with a specialisation in Dutch at the renowned department of the Karl Marx University in Leipzig. He comes from an intellectual family with father Jozef Bžoch as an eminent literary critic, mother Perla Bžochová as a translator from German and his sister Jana Bžochová-Wild also translates, mainly drama. After his education, he worked as a scientific researcher at the Slovak Academy of Sciences, taught for two years at the newly founded Department of Low Countries Studies at Comenius University in Bratislava and, in addition to his translation activities, headed the Department of World Literature at the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Until 2020, he also worked at the German language department of the Catholic University in Ružomberok, also offering courses in Dutch literature.

The scientific focus of Bžoch's research is psychoanalysis, conversation, the work of Walter Benjamin, Johan Huizinga and, in addition, a deep and extensive knowledge of Dutch literature. It is remarkable that apart from Elsschot's Kaas and a few poems and plays, he has not translated any Flemish literature.

Like Májeková, he received the Ján Hollý Translation Award for his translation of The Diary of Anne Frank and was also awarded a Dutch translation prize by the Dutch Literature and Production Fund in 2006. In addition, he was awarded a knighthood in the Order of Oranje-Nassau in 2008 for his exceptionally productive translation oeuvre. A selection from Bžoch's translation oeuvre shows a series of authors from the canon, at least one every year: Mulisch, Reve, Hermans, Bordewijk, Van Eeden, Emants, Couperus, Ter Braak, Nijhoff, Nescio, Rosenboom, Wolkers, Haasse, Springer, Huizinga, Abdolah, and many more. But it is also notable, that he prefers literature during the interbellum period, in addition to carefully choosing literature that enriches the Slovak readership with a certain aspect (see for example Brouwers' het Hout, Slauerhoff's Schuim en As, or Jan Arends' Keefman, with motives and a theme that deviate from the Slovak literary tradition). Besides novels, he also translated some poems, plays, a comic strip and some children's books.

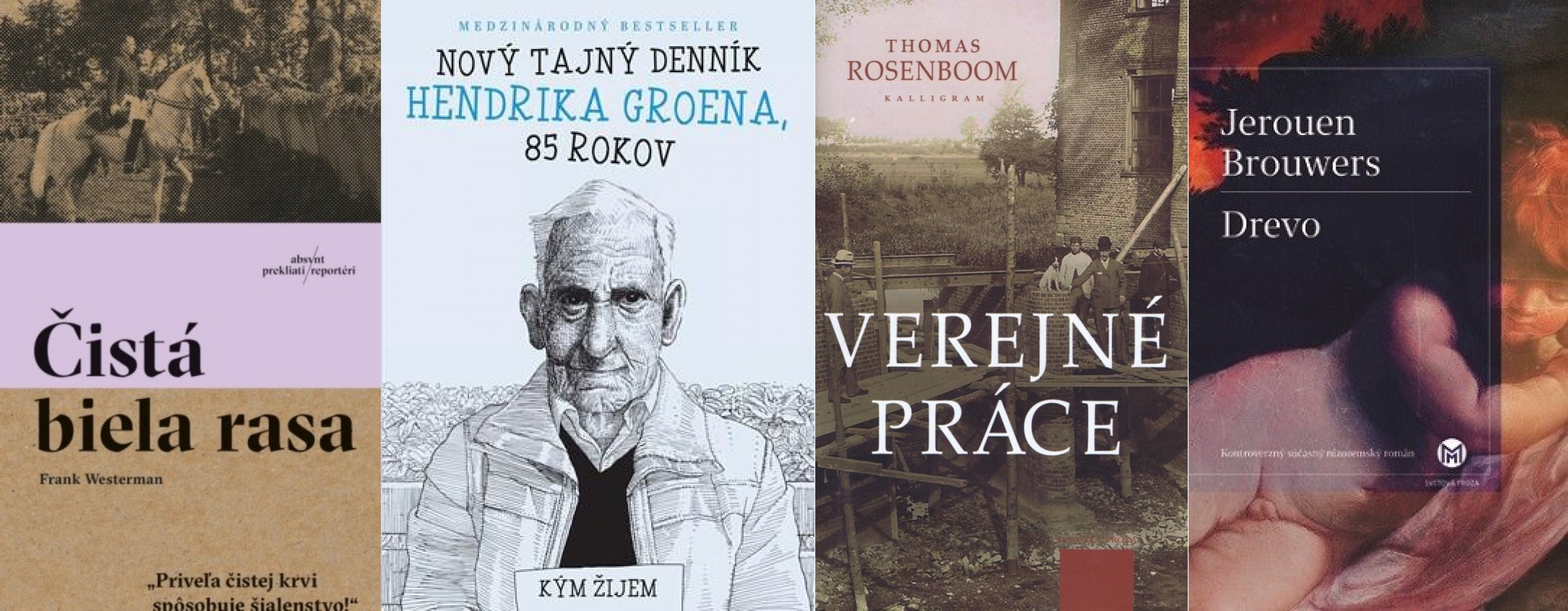

Apart from Adam Bžoch, after 1993 sporadic translations of fragments appeared, for example, in the above-mentioned literary magazine Revue svetovej literatúry (with a Belgian theme issue twice, 1998 and 2015). In addition, Bžoch's assistant at the Catholic University of Ružomberok at the time, Marta Maňáková-Blášková, also translated some novels (Thomas Rosenboom, Bernlef) and some other works have recently been published in translation, for example Dier, Bovendier by Frank Westerman by Annamária Vrbová-Gálová and the second and third part of the secret diary, Het geheime dagboek van Hendrik Groen by Zoran Oravec.

Four recent publications - all from different translators

(Benjamin Bossaert)

References

Bossaert, Benjamin. Belgické, flámske a holandské literárne lasagne. In: Revue Svetovej literatúry, Roč. 51, č. 3, 2015, s. 2-4

Bossaert, Benjamin. Pojem flámska literatúra na Slovensku. In: Revue Svetovej literatúry, roč, 54, č. 4, 2018, pp. 83-86.

Bžoch, Adam. Krátke dejiny nizozemskej literatúry. Ružomberok: Filozofická fakulta Katolíckej univerzity, 2010.

Engelbrecht, Wilken, Maňáková, Marta. Vertalingen van Nederlandstalige literatuur in Slowakije. In: Neerlandica Extra Muros (jg. 44), 2006, pp. 24-34.

Engelbrecht, Wilken. Van Siska van Rozemael tot Max Havelaar. Receptie van Nederlandstalige literatuur in Tsjechische vertaling van 1848 tot 1948. Lage Landen Studies 14. Gent: academiapress, 2021.

Heilbron, J. & G. Sapiro Outline for a Sociology of Translation: Current Issues and Future Prospects. In M. Wolf & A, Fukari (ed.), Constructing a Sociology of Translation, pp. 93-107. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2007.

Homola, Michal. Recepcia nizozemskej literatúry na Slovensku. In: Revue Svetovej literatúry, roč, 54, č. 4, 2018, pp. 87-91.

Kačírek, Ľuboš. Národný život Slovákov v Pešťbudíne v rokoch 1850 – 1875. Budapest: Croatica, 2016.