The Dutch Astrid Lindgren?

The story about how Annie M.G. Schmidt was introduced in Sweden by Astrid Lindgren

Annie and Astrid

In the Dutch language area Annie M.G. Schmidt (1911-1995) is commonly known as one of the great innovators of children’s literature of post-war times during the 20th century. Schmidt’s poetry for children has been praised for its playfulness and for the innovative ways in which it combines more traditional literary techniques with surprise elements of absurdist humor often connected to time relevant content and resulting in subtle forms of social satire in ‘child format’. Other very prominent characteristics of Schmidt’s writing are the use of (child) fantasy combined with a consequent child perspective, allowing the reader to see the world, most often ruled by adults, through the gaze of the innocent and unknowing child. This consequent use of child perspective provided a stark contrast and also a direct critique to previous (pre-war) traditions within children’s literature where morality prevailed and where child characters by rule were depicted from an adult perspective. At the same time, the renewing force in Schmidt’s authorship has to be placed in a broader social, cultural and literary context. The new child image and new way of writing for children also characterized the work and writings of many other European post-war authors of children’s literature, among which the most famous one was the Swedish Astrid Lindgren.

As several researchers have pointed out (see for example the research articles by Wikén Bonde, 1991; Waterstraat, 2010; Van Meerbergen, 2017), there are many similarities to be found between the work by Annie M.G. Schmidt and Astrid Lindgren. In the Dutch language area Schmidt even became referred to as the ‘Dutch Astrid Lindgren’ because of both personal and professional resemblances between the two authors, but also because of the similar and great impact both these ‘grand dames’ have had on the following generation(s) of children’s literary writers. Both were outspoken persons, they openly advocated for the rights of children, and they became publicly known figures within (and beyond) their time. Interesting to see is also that both were active in various ways within the media and/or publishing industry working a.o. as editors and translators of children’s literature and both also played an important role as cultural mediators of children’s literature within their own language area. It is then not by coincidence that Astrid Lindgren also came to play a key role in the translation and reception of Annie M.G. Schmidt’s work in Sweden.

A first Swedish translation wave in the 1950s and the 1960s

While Astrid Lindgren’s work soon became known and translated into many languages, the work of Annie M.G. Schmidt, in contrast, did not become equally successful and spread internationally. As is noted by the German researcher Kirsten Waterstraat, several of Schmidt’s works were for example translated into German throughout the years but this was done by several different publishers. By result Schmidt never managed to get a solid and stable position in the German children’s literary field. A similar pattern can be noticed in Sweden, where two translation waves took place for Schmidt’s work. Unfortunately, also in Sweden none of these translation waves has led to great success for the author in the Swedish children’s’ literary field. Interesting to see both in Germany and in Sweden is that it is mostly Schmidt’s prose for children that has been translated while her poetry, which has been hugely popular and up to this day still is well known in the Dutch language area, mostly is lacking in translation. A possible and reasonable explanation for this that has been put forward by researchers such as Ingrid Wikén Bonde and Kirsten Waterstraat is that the playful language, rhyme schemes, alliterations and ‘social satire’ in Schmidt’s poetry simply proved to be too challenging and too culture specific to translate into other languages.

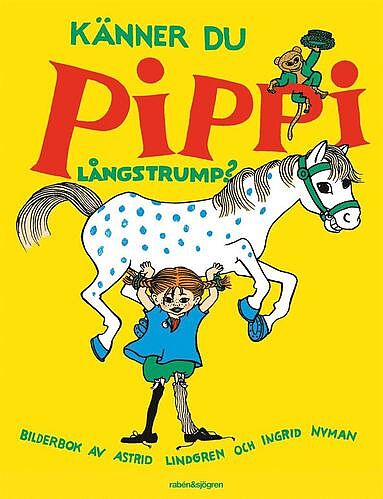

When looking at the first translation wave of Schmidt’s work in Sweden, surprisingly enough Astrid Lindgren herself proved to be the one that introduced Schmidt’s work in Sweden. During her twenty-five years as editor at Sweden’s most important and prominent publishing house for children’s literature Rabén & Sjögren (where her own work also was published), Astrid Lindgren functioned as an important ‘gatekeeper’ selecting and importing work from authors that she deemed as suited within the publishing profile of Rabén & Sjögren. During all these years Lindgren managed to establish a large (trans)national network and maintained contact with many foreign publishers in Europe, among which her own German publisher who allegedly brought Schmidt’s work to Lindgren’s attention. It is said that Lindgren recognized an important ally in Schmidt as a colleague female author with similar interests and that she was particularly attracted by Schmidt’s rebellious and bold way of writing. During the 1950s and 1960s four works of Schmidt were translated and published in Swedish by Rabén & Sjögren in relatively close succession to the original versions: Abeltje (1953, Swedish translation in 1957), De A van Abeltje (1955, Swedish translation in 1959), Wiplala (1957, Swedish translation in 1961) and Wiplala alweer (1962, Swedish translation in 1965). The translations were made by Saima Fulton (1897-1973), who translated a lot of children’s literature but also literature for adults from Dutch into Swedish in this period. The Swedish press reviews mainly praised Schmidt’s sense of humor and the way in which she elevated everyday language into a literary art form, which is described in more detail in the reception study about Annie M.G. Schmidt in Sweden by Swedish researcher Ingrid Wikén Bonde.

Interesting to notice is that Schmidt’s popular stories about the characters Jip en Janneke, that have been iconic and celebrated up to this present day within the Dutch language area, have not been translated at all into Swedish. The short stories about these child protagonists appeared as a series in the Dutch newspaper Het Parool during a couple of years from 1953 onwards. They were later on collected in a first book that appeared in Dutch original in 1960. No clear explanations for the Swedish non-translation of this popular series can be found, but as Wikén Bonde writes, it has been speculated that the stories and the characters were deemed to be too confirmative by the Swedish publishers compared to the more rebellious and anarchistic spirit that characterized Schmidt’s other work. After 1965 it thus became quiet around Schmidt in Sweden and no further translations were made until the second translation wave twenty years later.

A second Swedish translation wave in the 1980s

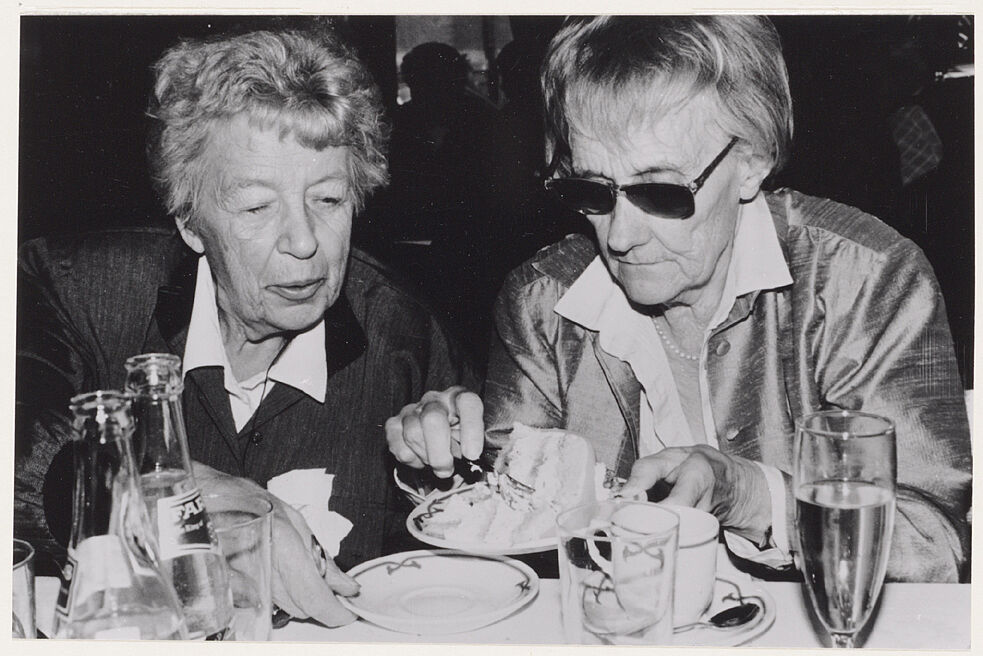

Astrid Lindgren and Annie M.G. Schmidt at the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 1988.

From: Altijd acht gebleven. NLMD/Querido, 1991.

The second Swedish translation wave came more exactly in 1989 when Schmidt’s youth novel Minoes, originally published in 1970, was translated into Swedish as Missan. The translation was made by Ingrid Wikén Bonde who worked as a translator of Dutch (children’s) literature and a senior lecturer in Dutch Studies at Stockholm University (see the interview with the translator Ingrid Wikén Bonde). This time the Swedish translation appeared at Berghs förlag, a smaller publisher with special focus on award winning international children’s literary authors. One year before the Swedish translation of Minoes Schmidt had received the most prestigious international literary award for children’s literature at that time, the Hans Christian Andersen Award. Yet again Astrid Lindgren’s and Annie M.G. Schmidt’s paths would cross, now for the first time in real life, as it was Astrid Lindgren who personally got to hand out the award to Schmidt at the award ceremony in Oslo in 1988.

The Swedish translation of Minoes received good reviews in the Swedish press, often comparing Schmidt’s style and her specific social engagement for the ‘weaker’ or marginalized groups in society with that of Lindgren. Still, no further translations of Schmidt’s work were made in Swedish after Missan. As is noticed by Wikén Bonde, one of the Swedish reviewers interestingly enough describes Missan as the Swedish debut of Schmidt. This shows that the first translation wave did not leave any large or permanent marks of Schmidt’s authorship, nor gave her fame, in the Swedish literary field. When the film version of the book Minoes came to the Swedish movie theaters in 2003, it appeared under a different Swedish title, Minou. Remarkably enough no new edition of the existing translation of the book was published by Berghs förlag, nor by any other publishers. When looking at the Swedish press reviews of the film, it is also notable that no mentioning is made of the (original) book and its Swedish translation from 1989.

To conclude the story of Annie M.G. Schmidt in Sweden, we can see that she never became as famous and successful in Sweden as in the Dutch language area, although she was introduced by a central and important figure such as Astrid Lindgren. Annie M.G. Schmidt will nevertheless continue to be remembered as the famous ‘Dutch Astrid Lindgren’, but this story will probably mainly be told in the Netherlands and Flanders. About the author: Sara Van Meerbergen is Associate Professor of Dutch Studies at Stockholm University. In her research she has a special interest for children’s literature in translation

(Sara Van Meerbergen, Associate professor in Dutch Studies, Stockholm University)

References

This text is based on: Van Meerbergen Sara (2017) Minoes in Zweedse vertaling. En over hoe Annie M.G. Schmidt in Zweden geïntroduceerd werd. In: Van Coillie J and Kalla IB (eds) Minoes, Minnie, Minu en andere katse streken: De internationale receptie van Annie M.G. Schmidts Minoes. Lage Landen Studies. Gent: Academia Press, pp. 77–93. Available at: urn.kb.se/resolve (accessed 27 October 2021).

Further references:

Waterstraat Kirsten (2010) De ‘echte’ en de ‘Hollandse’ Astrid Lindgren. Het werk en de receptie van Astrid Lindgren en Annie M.G. Schmidt - een vergelijking. Literatuur zonder leeftijd 24, pp: 31–46.

Wikén Bonde Ingrid (1991) Annie M.G. Schmidt in Zweden. Colloquium Neerlandicum 11, pp: 245–252.

· Here you can find all the Swedish translations of Annie M.G. Schmidt in DLBT:

· Here you can read an interview with translator Ingrid Wikén Bonde

· You can read more about Annie M.G. Schmidt, her life and her works on this blog: annie-mg.com

· See also Annie M.G. Schmidt on Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annie_M._G._Schmidt

· More information about Annie M.G. Schmidt’s books can also be found on the website of her Dutch publisher Querido: www.singeluitgeverijen.nl/querido/auteur/annie-m-g-schmidt-3/