War and Turpentine

The making of ‘a future classic’

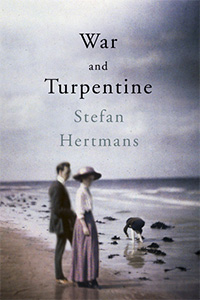

Oorlog en terpentijn (De Bezige Bij, 2013), by the Dutch-speaking Belgian author Stefan Hertmans, stands out as one of the few novels from Flanders to have achieved widespread circulation and success in the last half century. Not since Hugo Claus’s Het verdriet van België (De Bezige Bij, 1983) has a novel from Flanders travelled so well, so far, so quickly. In this post, we zoom in on the extraordinary reception of the book’s English translation, War and Turpentine (2016, translated by David McKay).

War and Turpentine is a creative re-imagining of the life and times of Hertmans’s soldier-artist grandfather, Urbain Martien. Distilled from the latter’s handwritten memoirs, which he entrusted to Hermans shortly before his death, it details Martien’s childhood growing up the son of a restorer of church frescos in late nineteenth-century Ghent, his experience fighting in the muddy gore of Flanders fields, and his long postwar life of dutiful marriage to his lost love’s sister. The book’s middle section is told from the perspective of Martien and unflinchingly describes the horrors at the front, where Martien is three times wounded and returned to the fight. Hertmans himself, or rather his textual surrogate, narrates the prewar and postwar sections that bookend Martien’s account, interspersing the story with Sebaldian visual realia, his own memories of his grandfather, and ruminations on how to piece together his family’s history.

Urbain, Stefan Hertmans’ grandfather and the book’s protagonist, in his soldiers’ uniform

Good things come to those who wait (sometimes...)

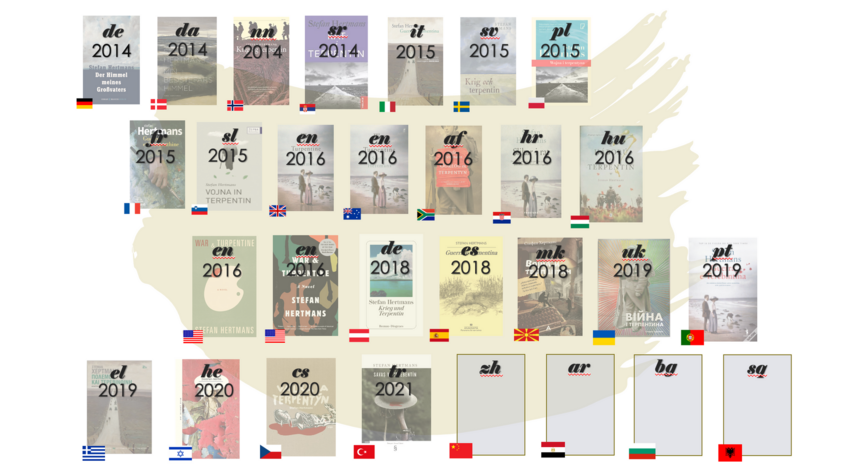

Oorlog en terpentijn was a runaway success in Flanders and the Netherlands. It was widely praised by Flemish and Dutch critics, has sold more than 200,000 copies in the Dutch original (quite a feat in a small market) and won the AKO Literatuurprijs, the most prestigious annual prize for literature in the Dutch language. It has since been widely translated, a rare achievement for a book from Flanders, which must first transcend a marginal position within a Dutch-language literary field dominated by publishers in Amsterdam, and then the peripheral position of the Dutch language in the world literary system where it circulates in translation. As of 2022, the book has been published in twenty-one languages alongside the Dutch original and translations in four more are currently in progress.

The book has also attracted international prize commendations: it was shortlisted for the Premio Strega Europeo in 2015 and the Best Translated Book Award in 2017 and longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2017 and the Dublin Literary Award in 2018. Its various translators have also won awards for their work. In most cases (but not all, as we will see), it met or exceeded its foreign publishers’ expectations in terms of critical reception and sales. This is unusual for a translated novel, as these tend to go unreviewed by critics and rarely cover costs. For De Bezige Bij, the book’s original publisher, War and Turpentine “was, together with Bonita Avenue by Peter Buwalda and Congo and Against Elections by David Van Reybrouck, the biggest recent worldwide hit we’ve had” (interview with Marijke Nagtegaal, March 16, 2018).

However, War and Turpentine struggled in some languages early in its transnational reception career and its later success was by no means guaranteed. The first translation to reach international readers was Hanser Berlin’s German hardback edition, published in December 2014. The book garnered less critical attention than anticipated in this important market, and sales were slow. The pattern of slow sales repeated itself in other first-wave language markets as well. It was beginning to look like War and Turpentine’s career beyond Dutch would play out the way those of most translated novels do: a positive but small reception, meagre sales and a short shelf life.

“A future classic”

The book’s makers held out hope for the English translation, which did not appear in the UK until June 2016 and in North America until September, nearly three years after translation rights were sold and well after many other first-wave translations had already come to market. The book did hit before one important deadline: the 100th anniversary of the end of the Great War.

In the weeks after its release in the UK, War and Turpentine was reviewed in Kirkus, The Sunday Times, Publishers Weekly, The Guardian and The Times. All were positive, but Neel Mukherjee’s review in The Guardian stands out as the most glowing and, as it turned out, most prophetic. He calls Hertmans “one of the great living Flemish poets” and praises the book’s blending of different generic conventions. Mukherjee closes his article with a bold consecratory proclamation:

”Urbain considered himself and his life ordinary. More than 20 years after his death, he has been given a kind of immortality by his grandson, an extraordinary afterlife that he never could have imagined. War and Turpentine has all the markings of a future classic.”

Mukherjee’s “a future classic” one-liner handed the book’s producers a golden blurb for their covers. It has thus far been used in front or back covers by six publishers, including De Bezige Bij in its latest reprint of the Dutch original, with surely more to come. By consecrating War and Turpentine in this way in The Guardian, Mukherjee was making the case for immortality, not only for the book’s flesh-and-blood protagonist, but also for the book itself.

Mukherjee is a Man Booker–shortlisted novelist and reviews two to three books a year for The Guardian. His interest in novels from Belgium stems from a stint in 2011 as a writer in residence in Brussels at the Passa Porta International House of Literature. Passa Porta supports literary exchange by bringing international writers to Brussels for residencies, seminars, readings and the biannual Passa Porta Festival. During Mukherjee’s stay, he became acquainted with important figures in Brussels’s literary circles, including Koen Van Bockstal, the former director of Flanders Literature, and Sigrid Bousset, Passa Porta’s director until 2014.

New wave

War and Turpentine’s strong reception in the UK would provide crucial momentum for a consecration every author and publisher longs for: a positive review in The New York Times. This appeared on August 5, 2016 in a Friday “Books of the Times” feature by fiction critic Dwight Garner who, echoing Mukherjee, praised the book’s canonic quality, calling it “old-fashioned” and “built to last”. Then, a (very rare) second review appeared sixteen days later in the Sunday edition by the writer Dominic Smith under the title “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Soldier”. On December 4, in the run-up to the holiday book-buying season, The New York Times included War and Turpentine on its list of “100 Notable Books of 2016” and a week later, capping a meteoric rise, the book was one of five fiction titles (and one of two translations) included in The New York Times “10 Best Books of 2016”.

The pattern of stagnant sales abroad had been broken: sales in the UK (the only anglophone market for which we were able to obtain data) topped 10,000 copies at the time, which its editor called “very successful for a literary international author’s debut in English” in her questionnaire response. It had taken more than four years of circulation in the transnational literary field, but Hertmans’s book was finally moving. The anglophone reception gave War and Turpentine a renewed transnational élan. Sigrid Bousset credits the anglophone reception, and particularly the “10 Best Books of 2016” mention in The New York Times, with stimulating “a new wave” of rights acquisitions. Rights for Spanish, Hebrew, Ukrainian, Chinese, Greek, Japanese, Macedonian, Portuguese and Turkish all would sell in late 2016 and early 2017. And so the making of “future classic” of world literature continues.

(Jack McMartin)

The covers of various translations of Oorlog en terpentijn in chronological order.