Dutch Second World War Diaries in Romanian Translation

There’s no wonder that diaries kept during the Holocaust have been and continue to be one of the most captivating types of documents which encourage reflecting on what should never happen again to humanity. A name like Anne Frank is perhaps the most famous when it comes to authentic testimonies from that period. Her journal not only made it into the universal non-fiction literature, but it also became one of the most translated Dutch books of all times. As significant as Anne Frank’s diary are also the writings of another two Dutch personalities, namely Last Stop Auschwitz by Eddy de Wind and An Interrupted Life: the Diaries, 1941-1943; Letters from Westerbork by Etty Hillesum, now both translated into Romanian.

Anne Frank’s diary and its way to the Romanian readers

Anne Frank’s diary was first published on the 25th June 1947 in the Netherlands, after her father, Otto Frank, received it from Miep Gies who had helped them hide in the Annex. She had managed to save Anne’s diary. The father was profoundly impressed by what she had written and decided to publish her diary, but not before removing critical paragraphs about Anne’s mother and other passages that were too intimate. He also chose to keep the pseudonyms of the other people hiding in the Annex and the real names of their family members. The dramatist and friend of Otto Frank, Albert Cauvern, also made some changes to the diary. After the article of the historian Jan Romein, Kinderstem, came out in the Dutch newspaper Het parool, the publishing house Contact from Amsterdam showed interest in Frank’s diary. After another 26 paragraphs were removed, the first published version came out under the original title Het Achterhuis. Dagboekbrieven van 12 juni 1942 – 1 augustus 1944.

In 1950 Anne Frank’s diary is translated into French and German. The first translation into German was made by the journalist Annelies Schütz, who was not a professional translator. For her translation published by Lambert Schneider (Heidelberg) she followed the modified version of Otto Frank and Albert Cauvern and changed some of the paragraphs where Frank shows a derogatory attitude towards Germany.

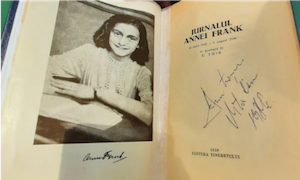

The first translation into Romanian of Anne Frank’s Diary, Constantin Ţoiu 1959

The first Romanian edition of Anne Frank’s diary was published in 1959 by Editura Tineretului (Bucharest), when Romania was already under the communist regime. The Romanian writer and translator Constantin Ţoiu translated it from the German edition published in 1957 by Fischer-Bücherei (Frankfurt). The Romanian edition opens with a foreword written by S. Damian (Samuel Druckmann), a Jewish essayist and important post-war literary critic born in Romania. He points out the symbolic value of the diary and its importance as a timeless memento of the abominations caused by the fascists. He takes a stand against the resurgence of fascistic propaganda powered by the imperialist occidental states during the ongoing Cold War. Furthermore, the Romanian critics of that time supported the same idea as S. Damian. In Steaua (The Star), the local magazine for art, literature, and culture, based in the Romanian city Cluj, the literary critic Toma Suciu wrote a book review, shortly after Anne Frank’s diary was translated into Romanian. He, as well, draws attention to the fascistic horrors that are still lurking in the background.

The first complete Romanian edition of Anne Frank’s Diary, 2011

The first Romanian edition of the complete version of Anne Frank’s diary in the translation of Gheorghe Nicolaescu was published in 2011 by publishing house Humanitas (Bucharest). The translation was subsidized by the Dutch Foundation for Literature, based on the complete Dutch version published in 2009 by Bert Bakker printing house (Amsterdam). According to the official website of Humanitas, the Romanian edition of the diary was one of the five bestsellers at the Gaudeamus book fair in 2011. But the success of the book did not stop there, because a new edition has just been published in April 2022 by the same publishing house. This edition celebrates 75 years from the first edition in 1947. This anniversary edition also includes photos of Anne Frank and her family.

When it comes to a comparison between the first and the most recent translation into Romanian, despite the different primary sources that served as a starting point for the translations, one can discover fascinating details for the Romanian translation of English terms, but also of realia. In the version translated directly from Dutch there are also footnotes for the German terms, which bring the Romanian translation closer to the original, in contrast to Constantin Ţoiu’s translation from German. Nowadays some of Ţoiu’s references might seem unnecessary for the modern reader, since he translates, for example, a term like “hobby”. Remarkable is that in Ţoiu’s translation of the diary page of Saturday, 15 January 1944, another footnote shows up for the English idiom “to make the best of it”, whereas in the recently published complete version this idiom doesn’t even appear in English. As a translation technique used in the latest Romanian version the domestication stands out, as for example in the notes of Monday, 6 December 1943, where the Dutch Sinterklaas is replaced by the Romanian sort of equivalent Moş Niculae (St, Nicholas Day).

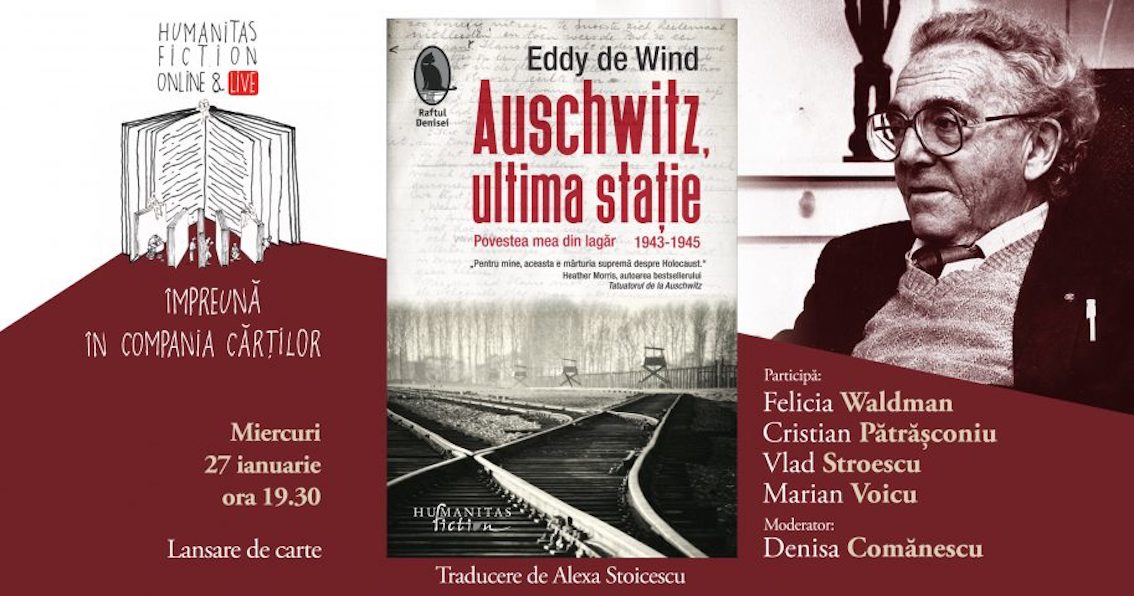

Last stop Auschwitz by Eddy de Wind: becoming a bestseller in Romania

Last stop Auschwitz, the only dairy written on the site of the camp, by the Dutch doctor and psychiatrist Eddy de Wind, who continued to live at Auschwitz after the end of the Second World War, was translated by Alexa Stoicescu and was published in 2021 by Humanitas under the title Auschwitz, ultima stație. Povestea mea din lagăr 1943-1945. This translation was subsidized as well by the Dutch Foundation for Literature. On the occasion of the book launch, Humanitas organized an online meeting where the focus was set on the biography of Eddy de Wind, but also on the fact that he wrote the diary in the third person. As regards to the Romanian translation, the fact that the specific German camp terms have been kept was highly appreciated, because of the authenticity it inspires to the text, as well as its approach to the original Dutch version. A milestone in the preparation of Alexa Stoicescu’s translation can be considered the book of Primo Levi, If This Is a Man (1947), where one can observe the very specific German camp terminology. In another online session organized by the Romanian online book trade Libris, in collaboration with Humanitas, the public could watch an interview with the son of Eddy de Wind, namely Melcher de Wind, and the Romanian writer and journalist Marian Voicu. Another interview with Melcher de Wind was organized by the same publishing house celebrating the International Holocaust Remembrance Day and was published in the Romanian newspaper Adevărul. Not only did the general interest in Holocaust testimonies spark the attention of the Romanian public, but it was also the marketing strategies of Humanitaswhich might have contributed to the fact that Last stop Auschwitz by Eddy de Wind ranks first among the bestsellers in January 2022, as shown by a Romanian paper.

Etty Hillesum’s diary and letters from Westerbork

Another book published in 2021 with the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature by Humanitas encompasses the diary of Etty Hillesum written between 1941 and 1942 and her letters from 1943: Jurnal (1941-1942). Scrisori din lagărul de la Westerbork (1943). As in the case of Anne Frank’s Diary, the testimonies of Etty Hillesum have been translated by Gheorghe Nicolaescu. The Romanian edition opens with a foreword written by Jan, G. Gaarlandt that was taken and adapted from the complete English edition of Etty Hillesum’s work (An Interrupted Life, 1996, Owl Books-Henry Holt and Company, New York). Between the text pages, there are also some pictures of Etty Hillesum and her beloved ones, as well as of different pages from her manuscript. In honor of the book launch, the already mentioned publishing house organized an online debate with the historian Alina Pavelescu, the journalists Cristian Pătrășconiu and Marian Voicu. An important element in their discussion is the polyphony of Etty Hillesum’s work, as it can be read from a feminist perspective, but also as a historical document depicting the oppression against the Nazis, where paragraphs dominated by eros meet confessions of a religious nature. Gheorghe Nicolaescu used footnotes for the German words that Etty Hillesum uses to reveal her philosophy of life. German was the language she used to show her love to the psychochirologist Julius Spier, the language to communicate with the Jewish refugees from Germany, but also a language of culture and literature, even though German was also the language of the enemy. The Romanian translation succeeds as well in finding the right tone that matches Etty Hillesum’s stream of consciousness, making her diary more introspective.

(Andreea Bălteanu)