Nijntje, Lilla kanin or Miffy?

Dick Bruna's Nijntje in Swedish translation

When looking at the Facts and Figures for Swedish translation of Dutch literature, the largest portion of translated titles consists of picturebooks for children. Among the most translated authors from Dutch into Swedish, counted in number of titles, is the Dutch children's literature author Dick Bruna. Bruna’s iconic and popular picturebooks about the protagonist Nijntje or Miffy, her international name, were translated into more than 50 languages and have been spread around the globe from the second half of the 20th century, but also after the turn of the millennium. Miffy’s popularity was to a large extend due to the immense merchandising that has been built up around this rabbit protagonist from the 1970s onwards, today under strict direction by the Dutch publisher Mercis. Even though not everyone would spontaneously connect the Miffy-character to picturebooks, many people do recognise the iconic visual depiction of the character which more or less has become like a brand on its own.

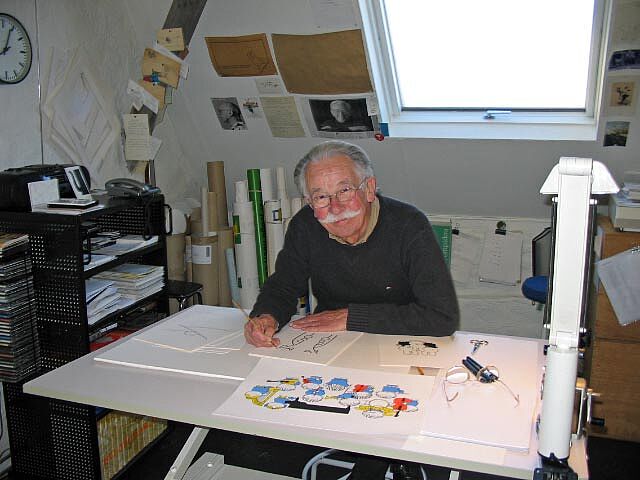

Dick Bruna

Picture by Dolph Kohnstamm

Dick Bruna (1927-2017) started off as a graphic designer designing book covers for the popular pocket series “Zwarte Beertjes” in the publishing house of his father, A.W. Bruna Uitgevers. He was particularly inspired by Picasso, Matisse and by the Dutch art movement De Stijl when creating his own series of picturebooks about the character Nijntje during the 1950s. De Stijl was active between the years 1917-1933 and several of its members became well known artists such as Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg and Gerrit Rietveld. In line with De Stijl Bruna used a strict and abstract design for his picturebooks which made the books stand out as bold, experimental and renewing when they first appeared. In line with the Stijl, Bruna uses a restricted pallet of basic colours and a small square format, which for example also can be seen in Mondriaan’s famous abstract paintings. Furthermore, the written text in Bruna’s picturebooks always consists of four lines in verse with a fixed and reoccurring rhyme scheme, printed in a specially designed type format in sans-serif and consistently lacking capitals. Throughout the years the small and square format of Bruna’s books has become a much-used format for picturebooks for young children, designed by Bruna in a functional way and with an eye on its young audience.

Two translation waves

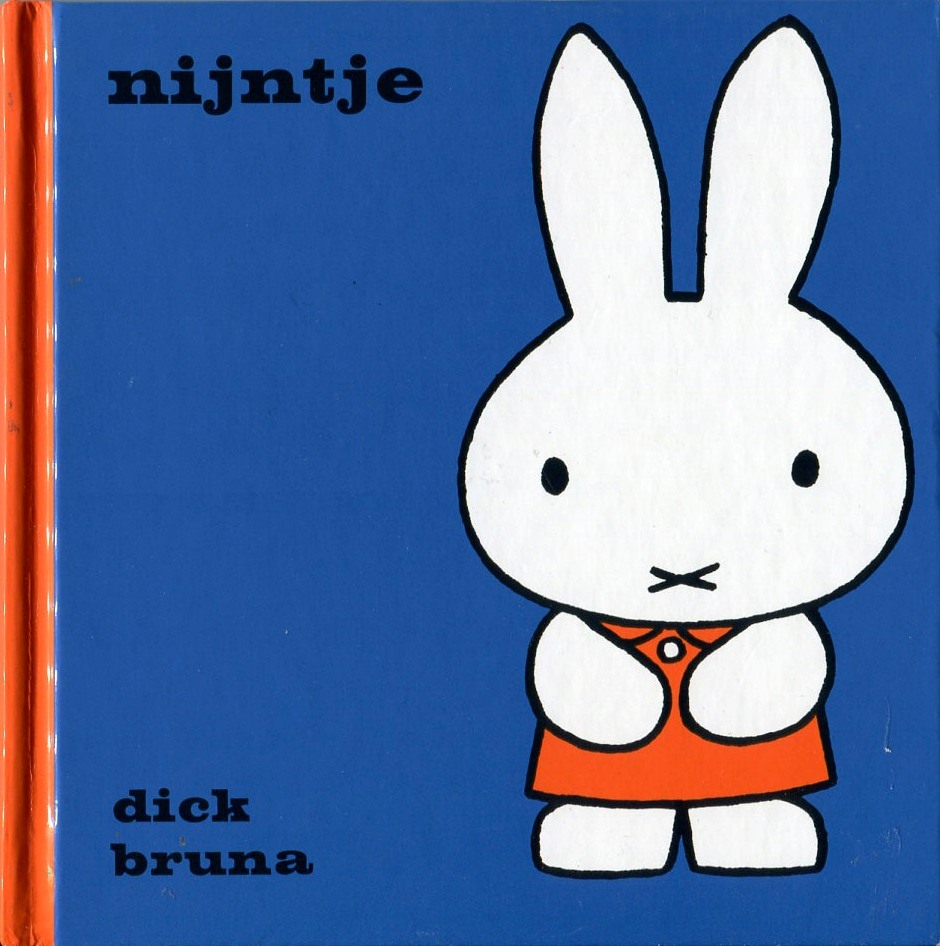

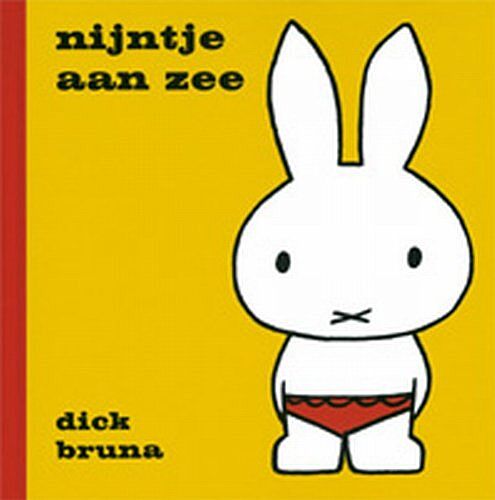

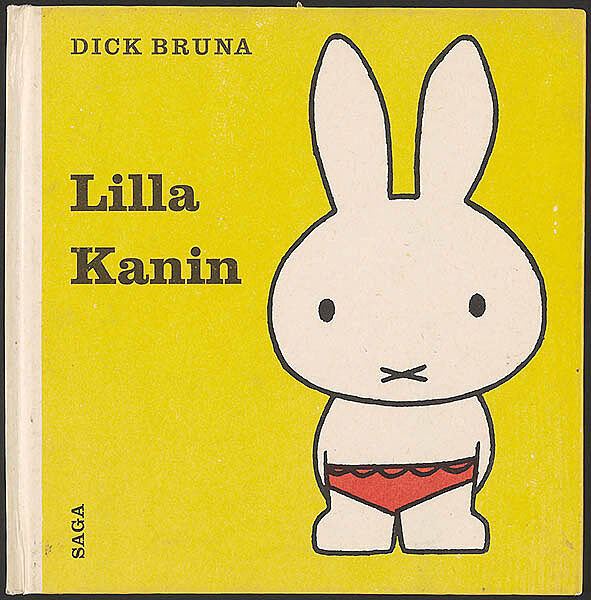

When it comes to the translation of Bruna’s books into Swedish, we can distinguish between two translation waves: a first one in the 1960’s and a second one from the 1990’s onwards. The first translations of Bruna came into being through a Nordic cooperation in the 1960’s. Letters of correspondence found in the archives of the Swedish Institute for Children’s literature (Svenska Barnboksinstitutet – SBI) show how the Danish, Finnish and Swedish publishers discussed certain criteria when together deciding on which of Bruna’s early titles they would translate and publish for the Nordic marked. These kinds of international co-productions were (and to a certain extend still today are) essential to press down on the costs when it comes to the publication of books with images in colour. The publishers decided on certain titles based on for example the colours of the covers (four different colours) and the main protagonists (two animal protagonists and two human protagonists). One of these first four titles was a first book about the rabbit protagonist Nijntje, which in Swedish received the name ‘Lilla kanin’ (‘Little Rabbit’), thus following the spirit of the Dutch name. Interesting to see is that the publishers chose to publish ‘Nijntje aan zee’ as the first book in the series about Nijntje and not the book ‘Nijntje’ which in Dutch was the first book in the series. In their correspondence the publishers state that they were not interested in publishing ‘Nijntje’ and thus actively chose not to do so, because this book contains ‘the birth of Christ in rabbit-format’ (‘Jesufödelsen i kaninformat’) which they did not find suitable for the Nordic child audience. This is a clear example of how social and cultural norms connected to a certain place and time can have an important impact on the selection and reception of children’s literature in translation.

In the early Swedish translations of Bruna’s books, the rhyme and metrical structure are kept in the Swedish versions showing an impressive effort and creativity from the translator’s side. The translator probably worked as an editor or publisher at Svensk Läraretidnings förlag, a Swedish publisher with an aim to publish qualitative books from all around the world (in that time mainly Europe) in easily accessible series for Swedish children. The documentation on the early translator is scarce which might also reflect that translation of children’s literature was seen as a lower status practice at that time. The translator is mentioned in the back of the books as the writer of the ‘Swedish text’, which also signals that the translations were done in a rather ‘free’ manner, deviating from the source text in order to fit the needs of the target audience. During the 1960’s 8 titles of Bruna were translated of which only 2 titles about Nijntje. A general trend in these early Swedish translations is that the moral tone in the Dutch stories is toned down and replaced by a lighter and more playful tone. Whereas Nijntje in Dutch represents a model child showing the child reader polite and proper behaviour, in Swedish Nijntje is liberated and represents a more ‘modern’ child view where play and fantasy become prominent in the story, following the spirit of influential post-war Swedish authors such as Astrid Lindgren and Lennart Hellsing.

Merchandising

The Miffy Shop in Amsterdam

In connection to a more general global new launching of Bruna’s books initiated by the Dutch publisher Mercis, the publishing house built around the merchandising and the books by Bruna, a second Swedish translation wave for Bruna’s books came in the 1990’s. In this translation wave the books about Nijntje, now called by her international merchandising name Miffy even in Swedish, are at the centre. The Swedish publisher Ordalagethas now taken over the translation and publication of Bruna in Sweden. Along with the classical picturebooks, Ordalaget also publishes many of the more commercial cardboard books about Miffy and they also take part in the distribution of other products related to the character of Miffy. The earlier Nordic co-productions are replaced by global co-productions with publishers all round the world, all directed by the Dutch publisher Mercis. In line with the earlier Swedish translations, rhyme and verse schemes are preserved in the new Swedish translations and Ordalaget continues to tone down the moral tone of the originals in subtle ways creating a product that they find more fitting for a Swedish child audience.

(Sara Van Meerbergen, Associate professor in Dutch Studies, Stockholm University)

Read more

You can read more about Dick Bruna and the Swedish translation of Nijntje in the following sources:

- Doctoral thesis on the translation of Dutch children’s literature into Swedish by Sara Van Meerbergen: Van Meerbergen, Sara, 2010. Nederländska Bilderböcker Blir Svenska En Multimodal Översättningsanalys. Stockholm: Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis. Available here.

- Article in Internationale Neerlandistiek about the Swedish translation of Dick Bruna: Van Meerbergen, Sara, 2012. “De kerk als een slagroomtaart. Een multimodale vertaalanalyse van veranderende kindbeelden in de Zweedse vertaling van Nijntje in de sneeuw”. Internationale Neerlandistiek 50(2). Amsterdam University Press: 4–19. Available here.

- Article in de Leeswelp about Dutch picturebooks in Swedish translation: Van Meerbergen, Sara, 2011. “Nederlandse prentenboeken worden Zweeds : Een multimodale vertaalanalyse”. de Leeswelp 17(1): 32–35.

- Article in Literatuur zonder leeftijd about Dick Bruna in Swedish translation: Van Meerbergen, Sara, 2010. “Dick Bruna in Zweedse vertaling : Een multimodale vertaalanalyse van kindbeelden”. Literatuur zonder leeftijd 24(81). DBN/ Biblion: 47–60.