Éditions de la Toison d'Or

Pre-war pacifists end europeanists Edouard and Lucienne Didier gradually veered to nazi sympathizers. They founded their publishing house at the start of World War II after the German occupying forces closed the Belgian borders to French books, wanting to publish French literary works within Belgium. In order to comply with the German propaganda requests, they also launched a collection of foreign and Flemish literature, publishing a total of one Dutch and five Flemish authors. Their collaborationist sympathies led to their flight and the disappearance of the publishing house in 1944, as well as to Edouard's conviction the following year.

The Éditions de la Toison d'Or were created in Brussels in 1941 by Edouard Didier, a printer, and his wife Lucienne, a notary's daughter and sculptor. In 1932, they had founded the movement Jeune Europe, for a federal and pacifist Europe. Lucienne, beautiful and charismatic, held a salon where personalities from all walks of life met: politicians and men of letters, Catholics, communists, rexists, socialists, Belgian, French and German.

Over the years, the importance they attached to Franco-German friendship, as well as, perhaps, a certain naivety [Cf. Dehan 1995: 218 and following] made them evolve towards collaborationist positions. In 1940, they were arrested on suspicion of intelligence with the enemy and imprisoned as hostages in France, but freed thanks to the intervention of their friend Otto Abetz, German ambassador in France. Lucienne continued to hold salons, both in Brussels and in Paris, where she received prominent personalities such as Henri De Man, Ernst Jünger and the Resistance writer Emmanuel d'Astier de la Vigerie, who would later intervene on their behalf after the war.

Éditions de la Toison d'Or

The publishing house project was born when the Didiers had just been released from their detention in France and were staying in Paris. Abetz testifies: "Finally, as the Belgian border had been closed to French books by order of the German authorities, Mme Didier and her husband proposed to found a publishing house for French literary works in Brussels itself in order to maintain intellectual contact between Belgium and French civilization. [...] This consideration was at the origin of the creation of the Éditions de la Toison d'Or". [Dehan 1995:224].

The daily management of the publishing house was in the hands of Raymond De Becker, journalist and soon-to-be editor in chief with the newspaper Le Soir. The official owners were the Didier couple, but in fact 135 of the 150 shares belonged to the Slovakian company Mundus, which was affiliated with the Nazi foreign ministry, headed by Joachim von Ribbentrop. The Amann Group, Mundus' main competitor, was dependent on the Propaganda Ministry headed by Joseph Goebbels, which sometimes would cause difficulties for the Éditions de la Toison d'Or. The publishing house had a branch in Paris in a private mansion that the Didiers occupied at the request of a friend who wanted to avoid a German requisition.

Publishing policy and catalog

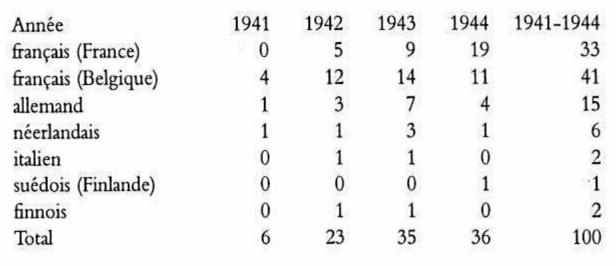

"The proposed publishing program ha[d] three points: the publishing of books, the publishing of a political-literary journal, and the exploration of young talent" (Fincoeur 1997:34), but the last two points would remain largely unheeded. As book publishers, though, they were rather productive. Still according to Fincoeur, between 1941 and September 1944, the Toison d'Or published 100 titles in 7 collections: mostly works of fiction plus a few historical and political essays. In principle, the historical and political essays were selected by De Becker, the works of fiction by the Didier couple. The busiest years were 1943 and 1944.

Our main interest here is in the Dutch and Flemish works that appear in the catalog. The German Ministry of Propaganda wished to reduce the predominant French influence in favor of a Germanic cultural influence. According to Simone Waslet, an employee of the publishing house, the publication of German and Scandinavian works (i.e., the collection “Lettres étrangères et flamandes”) was only a façade to satisfy the powers of the Occupation, Edouard Didier preferring to publish French titles [Dehan 1995:27].

Source : Fincoeur 1997 :38

Translations from Dutch

In the course of its four years of activity, the publishing house finally published six titles translated from Dutch, all works of fiction:

Gerard Walschap, Houtekiet (transl. Roger Verheyen, 1941, with an introduction by Guido Eeckels).

Filip de Pillecyn, Le soldat Johan (transl. Paul De Man, 1942)

Filip de Pillecyn, Hans van Malmédy (transl. Marie-José Hervijns & Georges Lambrichs, 1943)

Marcel Matthijs, Moi, Philomène (transl. Marie Gevers, 1943)

Multatuli, Max Havelaar ou les ventes de la société commerciale néerlandaise (transl. Edouard Mousset, 1943).

Gerard Walschap, Denise (transl. Robert de Vroylande 1944)

Two other translations from Dutch were announced, but never published: Albert van Hoogenbemt, L'homme silencieux (announced in 1943 on the cover of Eeckels' essay below), and Victor Leemans, Introduction à la sociologie (announced in 1942 in Le Nouveau Journal).

Also worth mentioning is an essay on Dutch poetry, written by Guido Eeckels: Marginales. Notes on Dutch lyricism (1943). Guido Eeckels, a rexist journalist who was soon to become director of the collaborating publishing house De Lage Landen was also a shareholder of the Toison d'Or publishing house, and he undoubtedly influenced the decision to publish two books by Walschap (the first of which he prefaced): he was the author of the first important analysis of Walschap in French and at the beginning of the war he wrote the column "Lettres flamandes" for Le Nouveau Journal [Fincoeur 2004: passim]. In 1968 he translated another Walschap title, Célibat, for the Editions Universitaires françaises.

The presence of Multatuli, the only Dutch author, can perhaps be explained by the presence of a French-speaking Dutch author in the publishing house's collection. Indeed, Neel Doff, whose Jours de famine et de détresse was published by Editions de la Toison d'Or in 1943, and who had herself tried her hand at translating Multatuli, was a faithful supporter of his work. Additionally, the themes of Max Havelaar are similar to those favored by the publishing house: escape, war stories, historical novels, anti-clericalism, denunciation of the bourgeois order [Fincoeur 1997:38].

Among the other published authors, Filip de Pillecijn and Marcel Matthijs were nazi collaborators. The decision to publish their novels may have been motivated by the desire to create a 'collaborationist façade' as suggested above. The same can be assumed for Victor Leemans, whose essay will not be published: he was a Flemish nationalist who sympathized with the Germans.

Translators

The complex political sympathies (or maybe the absence of true convictions) of the Didier couple are reflected in their choice of translators. Robert de Vroylande was initially a rexist, but from the mid-1930s onwards he attracted the enmity of Léon Degrelle, and was eventually deported in 1944. Georges Lambrichs is related to Jean Paulhan, a French Resistance publisher who was close to the Editions de Minuit), and Marie-José Hervijns appears to have had communist sympathies, while Paul De Man, nephew of the politician Henri De Man who was very close to the Didiers, had anti-Semitic sympathies. The author Marie Gevers was also close to collaborationist circles.

1944 marked the end of the publishing house: at the approach of the liberation, the Didier couple fled to France. They were arrested, but soon freed thanks to the intervention of Emmanuel d'Astier, who had become Minister of the Interior. No charges were brought against them in France; in Belgium, however, Edouard Didier was sentenced to death. The couple would spend the rest of their lives in France.

In addition to d'Astier's intercession, it is probably also their varied social acquaintances, as well as the somewhat ambiguous choices they made for their publishing house's catalog, that allowed the couple to escape legal proceedings in France. Thyssens writes on this subject: “I met Lucienne Didier in her Paris apartment, 51 rue de Seine, in November 1979. She had not kept any records, but she told me that the French National Security Directorate had, in 1946, conducted an investigation into the books published by the Toison d'Or, and had given her husband a certificate certifying ‘that after a thorough examination of the situation regarding the activity of the publishing house between 1940 and 1945, no charges had been retained against it.’” [Thyssens 2005-2021].

(Kim Andringa)

References

Xavier Dehan, “"Jeune Europe", le "salon Didier" et les "Editions de la Toison d'Or" (1933-1945)”, in Cahiers d'Histoire de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, XVII, 1995, 1, pp. 203-236, www.journalbelgianhistory.be/nl/system/files/article_pdf/cahiers_dehan_1995_1.pdf

Michel B. Fincœur, “Le monde de l’édition en Belgique durant la Seconde guerre mondiale : l’exemple des éditions de la Toison d’Or”, in Paul Aron, Dirk De Geest, Pierre Halen & Antoon Vanden Braembussche eds., Leurs occupations. L’impact de la Seconde Guerre mondiale sur la littérature en Belgique, Textyles hors-série n°2, 1997, pp.21-48, https://doi.org/10.4000/textyles.2245

Michel B. Fincœur, “Deux soeurs jumelles de la collaboration: les Editions de la Toison d’Or et l’Uitgeverij De Lage Landen”, in Dirk De Geest & Reine Meylaerts eds., Littératures en Belgique / Literaturen in België, Brussels: Peter Lang, 2004, pp.351-372

Henri Thyssens, Robert Denoël, éditeur; “Co-éditions” page, https://www.thyssens.com/02biblio/120coeditions.php