Dutch and Flemish literature in Serbia

In the beginning there was Conscience

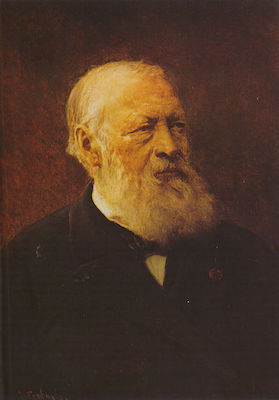

Hendrik Conscience, first author from the Low Countries to be translated into Serbian.

The first translation of a Dutch novel in the Balkans was published in the Kingdom of Serbia in 1868. It was the work of Flemish author Hendrik Conscience, The Miser (De gierigaard), originally published just fifteen years before its Serbian translation. Interestingly enough, four of Conscience’s works are among the five oldest translations of Dutch and Flemish literature in former Yugoslavia. In addition to this novel – also translated into Croatian as Škrtac by J. Zorić in 1893 – the short story “The Tear” (De Traan) was translated into Serbian around 1890. His major work, The Lion of Flanders (De Leeuw van Vlaanderen), was translated into Croatian by August Harambašić in 1906. This is not particularly unusual, since, in most countries in Central Europe, Conscience is the author whose work ushered in the reception of literature from the Netherlands.

The oldest Serbo-Croatian translations of Dutch and Flemish literature were indirect, and were produced mainly by using German as the intermediary language. In the period between the first translation and World War II, apart from Conscience, the audience in Yugoslavia, whose constituent part Serbia was at the time, had the opportunity to read the novels of Louis Couperus, Footsteps of Fate (Noodloot) and The Donkey in Love (De verliefde ezel), published in Zagreb in 1915 and 1923, respectively. There were also Stijn Streuvels and Felix Timmermans, with two works each, and Johan Fabricius, with his bestseller, The Girl in the Blue Hat (Het meisje met de blauwe hoed). Most translators from this period remain unknown. Their names were omitted or were mentioned by initials only. Furthermore, the reception of these translations in Yugoslavia hasn’t been researched, and aside from the forewords and afterwords, so far, few records about these works and the readers’ response to them have been found.

The first direct translations from Dutch

The first direct translations from Dutch did not appear until after World War II. One of the most prolific translators of this period was Josip Tabak, a Germanic and Romance language expert from Croatia. In 1975, Tabak produced a new Croatian translation of Conscience’s The Lion of Flanders – this time directly from the Flemish original – titled Lav od Flandrije. This was prompted by the realization that Harambašić’s existing translation, done via German, was far too liberal and riddled with errors. According to the biographical notes about the author:

“This situation with the Lion was truly a tangle […] Back then, Tabak spoke no Flemish, nor had access to the original (he would immerse himself into the language much later). Yet with the German translation in hand, he was already able to see that the Flemish writer spoke of one thing, and the Croatian translator another, often completely opposite… “

Later on, Josip Tabak learned Flemish and familiarized himself with Flemish literature and Conscience's great work in the original. It wasn’t until he extensively studied the novel and the context in which it was created that he decided to translate it into Croatian. For the purpose of his research, Tabak spent time in Flanders at his own expense on multiple occasions. This resulted in a comprehensive and very detailed afterword he wrote to accompany the translation, in which he introduces the readers to Flemish history, the inception of Romanticism in Flemish literature, and the author himself.

In the period following World War, all the way up to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, around seventy Dutch and Flemish titles belonging to fiction and children’s literature were translated into Serbo-Croatian. This period was marked by predominantly politically and socially engaged authors, such as De Vries, a communist, and Multatuli, a critic of Dutch colonialism. Other notable authors are Felix Timmermans, once one of the most translated and most prolific Flemish authors, and Stijn Streuvels, one of the most prominent figures in Flemish Naturalism.

Cover of the reissue of the Croatian translation of a picture book from the series about Miffy the rabbit from 2010.

A great number of titles from this period belongs to the genres of children’s and youth literature. Seventy titles from the picture book series about Miffy the rabbit (Nijntje), by Dick Bruna, one of the most famous Dutch children’s authors, were published in Zagreb between 1977 and 1986. Other authors worth mentioning are Miep Diekmann, a well-known children’s writer in the Netherlands from the 1950s to the 1980s, and Frans Hoppenbrouwers and his series of children’s books about animals, Poolsterreeks.

This period saw the emergence of translators who approached Dutch and Flemish literature in a more dedicated and studious manner. Apart from Josip Tabak, one of the most important translators is the Croatian translator and comparative literature professor Ivo Hergešić, who translated Multatuli’s novel Max Havelaar via German, and by consulting the Slovene translation. There is also the renowned Serbian writer, journalist and lexicographer, Dragoslav Andrić, who edited an anthology of young Flemish poets, and a collection of newer Flemish short stories, in which he included authors such as Willem Elsschot, Ernest Claes, Gerard Walschap, Louis Paul Boon, Hugo Claus and many others. Two professors from the English Department of the Faculty of Philology, Ranka Kuić and Mila Drašković, also contributed to the promotion of Dutch literature in Serbia, thanks to their personal ties to the Netherlands. As the wife of the ambassador, Mila Drašković lived in the Netherlands in the 1950s. There she met Den Doolaard whose novels, Roll Back the Sea (Het verjaagde water) and The Land Behind God's Back (Het land achter Gods rug), she would later translate via English (Novaković-Lopušina, 2010). It is important to note that this generation of translators are, at the same time, critics and reviewers of Dutch and Flemish literature.

An increasing interest in Dutch and Flemish literature

A significant rise in the number of translations of Dutch and Flemish literature in Serbia didn’t happen until the early 1990s. This period was also marked by a greater number of translators who translated directly from Dutch. Some of the most productive ones include Jelica Novaković-Lopušina, Ivana Šćepanović and Olivera Petrović van der Leeuw.

Cover of the Serbian issue of The Sorrow of Belgium from 2013. Arhipelag Publishing, Beograd.

Between 1990 and 2020, more than 200 titles of different genres, ranging from fiction and children’s literature to non-fiction, were published in Serbia (Budimir, 2020). The most translated author is the Flemish writer Hugo Claus, with ten titles published between 1995 and 2013. His best-known work, The Sorrow of Belgium (Het verdriet van België), translated by Ivana Šćepanović, was first published by Prometej from Novi Sad in 2000. Thirteen years later, Heliks, a publishing house from Smederevo, put out a revised edition. This novel is one of the rare translations from Dutch to attract the attention of critics. In his review, published in the Vreme magazine, literary critic Teofil Pančič points out that this work didn’t receive the attention it deserved when the translation was first published in Serbia, which he wishes to rectify with his review. Pančić states that “had Claus received the Nobel Prize (which he didn’t), I believe that The Sorrow of Belgium would, more or less, occupy the same place in our "general culture" as, let’s say, The Name of the Rose, One Hundred Years of Solitude or The Tin Drum; on top of that, Claus’ novel is better than all the ones listed…“ (Pančič, 2014)

In addition to Claus, other Dutch authors worth mentioning are Cees Nooteboom, with five translated titles, and Ivo Michiels and Adriaan van Dis, with four translated novels each.

During the 1990s, the works of Dutch and Flemish literature that were translated and published in Serbia were the ones written by the most important authors and those that belong to the Dutch literary canon. However, the year 2000 marked a turning point in the interest of publishers, who increasingly shifted their attention towards younger authors, best-selling titles, and award-winning books, especially those that won the European Union Prize for Literature. Between 2009 and 2020, this prize was awarded to three Dutch and two Flemish authors: in 2010, Peter Terrin, for his novel The Guard (De bewaker); Rodaan al Galidi, for The Autist and the Carrier Pigeon (De autist en de postduif) in 2011; Marente de Moor, for The Dutch Maiden (De Nederlandse maagd) in 2013; Christophe van Gerreway for Up to Date (Op de hoogte) in 2016; and finally, Jamal Ouariachi, for the novel A Hunger (Een honger) in 2017. All five titles were translated into Serbian soon after. There is also a noticeable interest in allochthonous/migrant authors such as Kader Abdolah, Hafid Bouazza, Rodaan al Galidi and others.

The period after 2010 is also characterized by the emergence of a younger generation of translators from Dutch, such as Srđan Nikolić, Bojana Budimir, Nevena Kukoljac and Mila Vojinović. All of these translators are graduates of the Department of Dutch Language, Literature and Culture at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade, and can be considered at the forefront of the third wave of translators from Dutch in Serbia.

(Bojana Budimir)

References

Budimir, Bojana. 2020. “Peripheries in the Global System of Translation: A Case Study of Serbian Translations of Dutch Literature between 1991 and 2015.” Dutch Crossing 44(2): 218-235. Article available online.

Novaković-Lopušina, Jelica. 2010. “Zuidslavische enthousiastelingen.” In Neerlandistiek in Europa. Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van de universitaire neerlandistiek buiten Nederland en Vlaanderen, edited by M. Hüning, J. Konst and T. Holzhey, 277-292. Münster/New York/München/Berlin: Waxmann (Niederlande-Studien, 49). Article available online (in Serbian).

Pančić, Teofil. 2014. "Remek delo iz nemoguće zemlje". Vreme, Vol. 1214 (10.04.2014). Available online.