‘The Novel that Killed Colonialism’

'Max Havelaar' in a New English translation for Postcolonial Times

In 2019, the New York Review of Books published a new edition of Max Havelaar, of de koffiveilingen der Nederlandsche Handelsmaatschappij (1860) in a new and updated translation by Ina Rilke and David McKay. Often considered the greatest nineteenth-century Dutch novel, Multatuli’s powerful indictment of the abuses of the Dutch colonial administration in the Dutch East Indies found a new Anglophone readership.

“‘The book is multifarious… disjointed… straining for effect… the style is poor… the author inexperienced… no talent… no method…’ Fine, fine, all of it fine! But… THE JAVANESE ARE MISTREATED! THE MAIN POINT of what I have written is irrefutable!”

The so-called ‘Sjaalman portrait’ of Multatuli. Reproduced in: Dik van der Meulen, Multatuli: leven en werken van Eduard Douwes Dekker . (Amsterdam, 2002)

These words fill the final pages of Max Havelaar; or, The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company. Written in 1860 by Multatuli, a pen name of Eduard Douwes Dekker, the book caused a political firestorm upon publication. Max Havelaar remains required reading for students of Dutch literature and is to the Netherlands what Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) is to the United States.

Max Havelaar paints a damning picture of 19th-century Indonesia under Dutch colonial rule. Although Multatuli’s text has been fortunate to generate a number of English translations over the decades (the first one appeared a mere eight years after publication of the Dutch original), its latest, commissioned by the New York Review of Books and published in 2019, is among its most notable. Following fifty years after Roy Edwards’ celebrated but by now outdated translation for Penguin Classics, this fully new translation was produced by Ina Rilke and David McKay, two translators from different regions and generations who felt “it was of prime importance to give this new English version an up-to-date sound”.

More inclusive and progressive advances in our society aside, it is perhaps Max Havelaar’s explosive nature that attracts contemporary readers. Multatuli’s text was considered so controversial by its first publisher Jacob Van Lennep that he set about altering the novel to tone down its political volatility. A copy of that first edition, as censored by Van Lennep and with dates and names of people and places omitted, is housed in the British Library. It wasn’t until 1875 that Multatuli was able to buy back the copyright of his own novel and have Max Havelaar published with the original names and dates re-inserted. In the later editions of Max Havelaar published during the author’s lifetime, Multatuli included extensive notes. Rilke and McKay’s new translation includes the large majority of those notes, which show how his views evolved over time and provide a fascinating additional layer of narrative. A few have been abridged or left out for various reasons; for instance, some deal with linguistic concerns irrelevant to the English version.

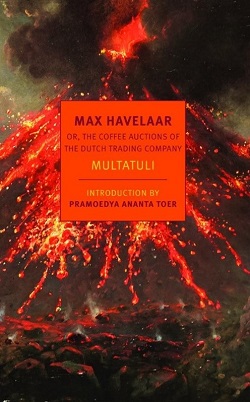

The cover image of the latest English edition clearly hints at the explosiveness of Multatuli’s work: Indonesian artist Raden Saleh’s painting of Indonesia’s most active volcano, Merapi, meaning “the one making fire” in old Javanese, occupies the front cover. A fitting choice for the book that, according to the Indonesian writer Pramoedya Anata Toer, “killed colonialism.” What made Max Havelaar so politically charged was Multatuli drawing attention to the suffering of those dominated by colonial rule. Multatuli was considered an extraordinary thinker for his time – he wrote about his experiences with the local population in Indonesia not as their oppressor, but as someone determined to be their ‘saviour’ – although this sense of white responsibility is of course also part of the colonial mindset.

Front cover of Max Havelaar or, The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company (New York, 2019)

Whether Multatuli’s motivations for writing Max Havelaar were purely self-serving – he wanted his job as a colonial administrator back – or whether he wrote to campaign for better conditions for the Indonesians, it was essential for him to present Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia in a critical light. One of his most effective tools was altering Dutch readers’ perceptions of the native Indonesians, countering Orientalist descriptions and portraying Indonesians as victims of colonialism. A key example of this is the enduring story of Saidjah and Adinda, which depicts a pair of Indonesian star-crossed lovers. This tale is perhaps the most well-known from Max Havelaar and has been published as a separate story numerous times, although a separate English edition of this tragic tale of love and loss at the hands of ruthless oppressors is not yet available.

Multatuli’s writing style, which sees him break into the narrative as the righteous omniscient narrator who speaks truth to power, made Max Havelaar all the more persuasive. This style, innovative to readers back in colonial Europe and still so fresh today, earned the text its reputation as a literary masterpiece. More than 160 years on, the themes of the novel still resonate – questioning those that hold power and bringing about emancipation for the subjugated remain ever-significant. Max Havelaar continues to entice readers worldwide, both as a novel and as an indictment of oppression that brought about a decisive change in policy and national mindset. The latest English translation by Rilke and McKay extend this appeal to contemporary Anglophone audiences and debates.

(Megan Strutt & Filip De Ceuster)

References

Ananta Toer, Pramoedya: ‘The Novel that Killed Colonialism’. In: The New York Times, section 6, p. 112, 18 Apr., (1999).

Anon.: ‘Multatuli: Max Havelaar or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company’. (s.d.) https://www.letterenfonds.nl/en/book/928/max-havelaar

Multatuli: Max Havelaar or, The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company. New York: New York Review of Books, (2019).